Introduction of Photography in Iran

According to scholars and historians, the first photographer in Iran was Jules Richard, a Frenchman who, as stated in his diaries, arrived in Tehran in 1844. He served as the French language tutor of the Gulsaz family and took daguerreotypes of Mohammad Shah (reigned 1834–48) and his son, the crown prince, Nasir al-Din Mirza. To date, none of these early images has been located. Richard’s presence at the court is recorded in the 1888 Al-Ma’sir va al ‘Asar, a forty-year history of Iran compiled by I’timad al-Saltana, one of Nasir al-Din Shah’s confidantes. Photography subsequently became a serious pastime for Nasir al-Din Shah following his coronation in 1848 (fig. 1).

A decade later, several photographers active in Tehran introduced new techniques. Many of them were army officials or personnel attached to various foreign commissions. August Kriziz, an Austrian artillery officer who taught at the new polytechnic school, the Dar al-Funun, in the 1850s, experimented with calotypes.1 Mr. Focchetti, another instructor at the Dar al-Funun, is credited with introducing the collodion process to Iran.2 In the 1860s, two Italian photographers Luigi Montabone (died 1877) and Luigi Pesce (1818–1891) were also active in Iran in the 1860s.3 The most prolific among these early European photographers was Ernst Hoeltzer, a German engineer who was employed by the Indo-European Telegraph Department. Some three thousand glass plate negatives that Hoeltzer created while he lived in Iran from 1863 to the mid-1880s have survived and are today in the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, the Netherlands.

Fascinated by the new medium and its potential, Nasir al-Din Shah in 1863 appointed one of his favorite court attendants, Aqa Riza Iqbal al-Saltana, to learn the techniques of photography. Sometime in the 1860s, an official position was created for a court photographer, and the darkroom and photographic studio of the Gulistan Palace were in full function. In addition, the Dar al-Funun established its own photographic studio and atelier.

Nasir al-Din Shah himself became an avid photographer and in the mid-1860s began taking images of the women and eunuchs of the court—and even of his cat. Allegedly, both the shah and his court photographer received instruction from the French photographer Francis Carlhian (1818–1870), who joined the court at the specific request of Nasir al-Din Shah and his vizier, Amin al-Dawla. Carlhian not only served as the shah’s teacher (although he was never officially noted as such), but he was also responsible for bringing the medium to the attention of a wider public by importing and selling photographic equipment.

The shah’s affinity for self-portraits inspired him to teach the art of photography to another court attendant, known as Muchul Khan. Since he was also helping Nasir al-Din Shah develop and print his negatives in the royal darkroom, Muchul Khan became a trusted collaborator and was even allowed to take photos of the harem women.

By the 1870s, Nasir al-Din Shah had at least three official photographers (in addition to Muchul Khan) who accompanied him on his travels both inside and outside the capital. On his three travels to Europe (1873, 1878, and 1890), the Qajar ruler made entries in his diaries about his personal visits to well-known photographic studios. When he visited Istanbul, for example, he noted that the official court photographer, Abdullah Khan, took his portrait. Nasir al-Din Shah also commented on the quality of the Ottoman photographer’s work and technique, claiming, “Abdullah Khan khub akz miandazad”(Abdullah Khan takes good photographs).

Among the early independent photographers in Tehran was Joseph Papaziyan, who opened a studio around 1875. Years later Nasir al-Din Shah bestowed one of the most revered medals of the Qajar court on this Armenian Iranian photographer. Little is known about the activities of Papaziyan’s studio, but a few of his photos are in the archives of the Gulistan Palace Museum in Tehran. His photographic prints—decorated on the reverse with an elaborate design in four languages—provide the studio’s name, its date of establishment, and an impression of the Medal of Lion and Sun.

The other successful commercial studio in Tehran in the late nineteenth century belonged to Antoin Sevruguin (died 1933). Born in Tehran and trained in Tbilisi, Sevruguin established a studio first in Tabriz in the early 1870s and then in Tehran later in the decade. He soon became one of—if not the most—prolific and accomplished photographers of the capital city. His studio was a destination for the royal family, foreign visitors, and locals (fig. 2). Several devastating incidents marred Sevruguin’s career, including a bomb explosion in 1908 that was aimed at the house of his neighbor Zia al-Dawla, an avid supporter of the constitutional revolution. The bomb destroyed most of Sevruguin’s extensive collection of glass plate negatives. His later attempt to add motion pictures to his professional ventures proved a failure. Yet, Sevruguin persevered as a photographer, and his works can be found in many public and private collections both in Iran and outside the country, with the most notable among these being the Freer and Sackler Archives and the Gulistan Palace Museum in Tehran.

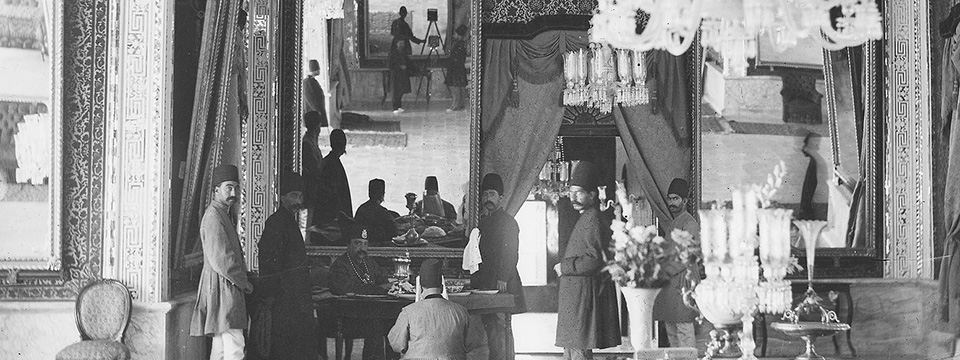

As early as 1885, Sevruguin’s photographs of landscapes and people of Iran were published in international newspapers, magazines, and books (fig. 3). His impressive collection of glass plate negatives in the Freer and Sackler Archives attests to a diverse range of subjects and interests, with a particular emphasis on dramatic lighting and exquisite composition (fig. 4). In some of his works, Sevruguin inserted himself into the composition, thus establishing his presence and that of the camera in the scene. Whether depicting the monumentality of Persepolis or a session at court (fig. 5), the photographer’s reflection or shadow at once personalized the image and transformed it into a self-portrait. Trained as a painter, Sevruguin also tended to manipulate his negatives to enhance their dramatic effect. A tree added here, a tiny balustrade cleaned up there, he personalized many of the photographs and left his trace on them.

In addition to public studios and ateliers, wealthy aristocrats established their own home studios and darkrooms, sent their sons to Europe to learn photographic techniques, and acquired a taste for studio portraiture. Mu’ayyir al-Mamalik, head of Nasir al-Din Shah’s treasury, for example, sponsored the European travel of the photographer Abdullah Mirza Qajar (1850–1909) to learn modern processes as well as photolithography. On his return in the late 1870s, Abdullah Mirza initially worked in the publishing house of the Dar al-Funun, and from 1883 he served as the official photographer of Nasir al-Din Shah’s court until the king’s death in 1896 (fig. 6). Abdullah was sent around the country to photograph new buildings and their construction, and he accompanied Muzaffar al-Din Shah (reigned 1896–1907) on his first trip to Europe.

The first decade of the twentieth century saw a remarkable proliferation of photography in Iran thanks to the introduction of more portable and affordable photographic equipment. By the end of the first decade, photographic studios and shops moved beyond the major cities and were established throughout the country, which greatly contributed to the incorporation of photography into daily life. The popularity of family albums and studio portraits testify to photography’s rapid dissemination and acceptance, while images by well-known photographers were reproduced on postcards and royal stationery. By the 1920s, newspapers and magazines started to illustrate articles with half-tone photographs. A mere fifty years after its public introduction to Iran, photography was seamlessly integrated into the fabric of daily life there (fig. 7).

Notes

1. In this early process of making a negative, paper was sensitized to light by coating its surface with silver iodide. The British photographer William Henry Fox Talbot first introduced the process in 1841.

2. Introduced by Fredrick Scott Archer in the 1850s, the collodion process consisted of coating a glass plate negative with a light-sensitive formula dissolved in collodion immediately before taking an image. Although the process was labor intensive and required a portable darkroom for coating the plates, it greatly appealed to photographers for its ability to capture fine detail in a short exposure time. It effectively replaced all other methods of producing negatives until the 1880s, when it was replaced by the dry-plate technique.

3. Montabone accompanied an Italian mission of sixteen political, scientific, and military officers to Iran in 1862. Originally from Naples, Italy, Colonel Pesce went to Iran in 1852 to train military officers.

- The Collections

- Antoin Sevruguin

- Abdullah Mirza Qajar

- Essays

- Recent Acquisitions

- About the Archives

- Donate Your Photos