PROGRAM NOTES

Renaissance Songs of Travel: Vozes Alfonsinas

Listen Now

download

Subscribe (itunes)

Subscribe (rss)

help

Program

La Mar de la Musica: Songs of Departure and Return

Vozes Alfonsinas

Manuel Pedro Ferreira, director

Maria Repas, soprano

Susana Teixeira, mezzo-soprano

Gonçalo Pinto Gonçalves, tenor and percussion

Vítor Gaspar, baritone

César Viana, recorders and percussion

Madalena Cabral, rebec

Nuno Torka Miranda, Renaissance guitar and vihuela

André Barrosa, theorbo

This concert took place on July 26, 2007, at the Freer Gallery of Art in conjunction with the exhibition Encompassing the Globe: Portugal and the World in the 16th and 17th Centuries. The podcast is made possible through support from the Thaw Charitable Trust. Audio preservation and editing of this recording were supported by funds from the Smithsonian Women’s Committee.

Juan del Encina (1468‒1529/30)

- Vilancete: Un’ amiga tengo, hermana (Cancionero de Palacio)

Anonymous

- Vilancete: Porque me não vês, Joana (Cancioneiro de Elvas)

Diego Ortiz (ca. 1510‒ca. 1570)

- Recercada prima

Luís Milán (ca. 1500‒ca. 1560)

- Vilancico: Um cuidado que minha vida tem

Anonymous

- Cantiga: Parti ledo por te ver (Cancioneiro de Elvas)

Miguel de Fuenllana (act. 1553–1578)

- Endechas de Canarias: Si los delfines mueren de amores

Anonymous

- Vilancete: Cuidados meus tão cuidados (Cancioneiro de Elvas)

Luís Narváez (1500‒ca. 1555)

- Variations on the melody of Guardame las vacas

Anonymous

- Vilancete: Sempre fiz vossa vontade (Cancioneiro de Elvas)

- Vilancete: Parto triste, saludoso (Cancioneiro de Elvas)

Diego Ortiz

- Recercada a solo

Anonymous

- Canarios

Anonymous

- Vilancete: Ojos tristes non lloreis

Luís Milán

- Vilancico: Levay-me, Amor, daquesta terra

Diego Ortiz

- Recercada seconda

Gil Vicente

- Romance: Ninha era la infanta (Cancioneiro de Lisboa)

Anonymous

- Chaconas (dança)

Francisco Martins (ca. 1620 or ca. 1625‒1680)

- Vilancico: Sentado ao pe de hum rochedo

Anonymous

- Guineo (dança)

- Vilancico: Sã qui turo zente pleta (negro)

Listen Now

download

Subscribe (itunes)

Subscribe (rss)

help

Notes

La Mar de la Musica: Songs of Departure and Return

The conquest of the Atlantic Ocean altered not only the history of Portugal but also its music. Up until the seventeenth century, the Portuguese nation was intimately connected to neighboring Spain. The discovery and populating of the Atlantic islands and the exploration of the west coast of Africa left their mark on the Iberian musical panorama of the sixteenth and seventeenth century. The musical influence of the colonization of the Americas became apparent later.

Just as wine returns from a journey with characteristics different from those it originally had, so Iberian musical culture, once tempered by the Atlantic experience, acquired new compositional flavors. This performance calls attention to these outside influences by presenting some written vestiges of this “music of the return journey,” the greater part of which, dependent on oral tradition, has perished in the vortex of history.

In elevated social circles of Portugal culture during this period, music of a more elaborate kind did not, at first, allow itself to be affected by overseas influences. In vocal music, the themes of distance and love-stricken yearning, in spite of their renewed relevance, do not seem to have particularly interested composers in the 1500s. The lyricism typical of the polyphonic song of the time is here illustrated by songs in Portuguese: “Porque me não vês, Joana” (no. 2), “Cuidados meus tão cuidados” (no. 7), and “Sempre fiz vossa vontade” (no. 9). These are anonymous pieces taken from Portuguese songbooks, where “Ojos tristes” (no. 13), here performed by instruments, is also found. In strictly instrumental music, variations on a fixed harmonic pattern became fashionable around the middle of the sixteenth century (no. 8); the free Recercadas (nos. 3, 11, 15) won an unexpected artistic prominence in the hands of Diego Ortiz.

The three Castilian songs in this concert have a different, contrasting character. “Un’ amiga tengo, hermana” (no. 1) by Juan del Encina explores a light, humorous vein; “Parto triste, saludoso” (no. 10) glosses the sadness of departure and separation; the tempestuous sea waves are used for striking poetic effect in “Parti ledo por te ver” (no. 5). An exceptional direct reference to travel by sea is found in the romance “Ninha era la infanta” (no. 16), a narrative song on the departure of young princess Dona Beatriz from Lisbon to get married in 1521. The text is found in a play written by Gil Vicente to commemorate the occasion and also (in a fragmentary, different form) in the Lisbon Songbook, from where the present musical version is taken. Here, the princess, still a child, is presented as the granddaughter of the king of Castile and as the daughter of the king that all kings of the Far East respect the most (i.e., the king of Portugal). The longer version is also given below, for comparison.

Visible in the popular imagination expressed in the texts of songs and ideas associated with dances is the influence of maritime legends: not the darker ones inhabited by monsters and bottomless deeps, but those with more enchanting qualities, such as friendly dolphins and fantastic lost islands. These myths were fed not only by sea journeys but also by contact with the primitive inhabitants of the Canary Islands, which were rediscovered by the Portuguese before 1336 and were disputed for more than a century between Portugal and Castile.

The expression Endechas de Canarias (no. 6) refers to a sentimental song alluding to dolphins. It was inspired by the plaintive and sorrowful melodies of the aborigines of the islands of Hierro and Gran Canaria. The version of the Endechas used here is that transmitted by Miguel de Fuenllana, who was in the service of King Sebastian of Portugal (1554–1578) from 1574 to 1577. Also of indigenous inspiration are the Canarios (no. 12), stylized dances that became particularly popular around 1600. The leaps and taps typical of this dance were especially vigorous, leading one writer of the period to insinuate that the Canario was nothing more than “tapping feet.”

The mythical “lost island,” a paradisiacal that expressed desires of earthly happiness, is the utopian horizon of the song “Levay-me, Amor, daquesta terra” (no. 14) by the celebrated vihuelist Luís Milán, who also composed “Um cuidado que minha vida tem” (no. 4). Milán dedicated his book El Maestro, the source of these songs, to the Portuguese king John III (1502‒1557). This explains the choice of Portuguese texts alongside Castilian ones. The following eulogy is part of the dedication: “The sea upon which I have launched this book is, piously, the kingdom of Portugal, which is the sea of music: for there it is as esteemed as it is understood.” The rhetorical context in which the expression “the sea of music” appears should not allow us to forget that at the Portuguese court, nourished by maritime commerce, the Atlantic experience was able to influence, more so than elsewhere, informal musical practices, particularly dances.

At the end of the sixteenth century, the mythical “lost island” acquired the name Chacona. There, everything was said to be abundantly available, which explains the popular refrain, “The good life, the good life, now we’re off to Chacona.” The nameChacona was given to a sung dance that was considered to be shockingly erotic; the instrumental Chaconas (no. 17) included in this concert derive from this same dance.

While the theme of leaving is taken up in some vilancetes (Portuguese for early villancicos) and cantigas (Spanish: canciones), travel is rarely referred to in polyphonic works. “Sentado ao pé de hum rochedo” (no. 18), by Francisco Martins, presupposes distance from the loved one. Although it concentrates on the idea of longing, it also has a religious facet, in that the yearning may be understood metaphorically as longing for Christ, which justifies the association of this villancico with the Ascension.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, most men of working age were engaged in non-productive activities, and the Iberian economy resorted to slave labor. The cultural repercussions of importing black slaves from the coast of Guinea are, as far as music is concerned, hardly documented and little studied. It is clear, however, that percussion instruments invaded the streets. In the realm of theater appeared the negro, a subcategory of the villancico that is distinguished not only by the language employed—a proto-Creole based on Portuguese—but also by a strong rhythmic character that at times shows African influence. No sixteenth-century negros survive with their music.

The villancicos from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century developed around the celebration of Christmas and Epiphany, festive occasions that were naturally spectacular and therefore attracted a great many faithful. In the negro “Sã qui turo zente pleta” (no. 20), sung in Coimbra at Christmas 1647, the texture is relatively simplified, but the number of voices (eight), though modest, already expressed the noticeable taste for poly-chorality that would characterize Iberian music of the seventeenth century. The syncopated rhythms and responsorial acclamations are made to echo African traditions then alive in Portugal.

As with the negro “Sã qui turo,” the Guineo (no. 19) is a dance that took its inspiration from the culture of the black slaves from the coast of Guinea. Moreover, a negro for voices could also be called a Guineo: the term was used with a certain flexibility. The gestures associated with the Guineo dance could be considered improper, or even indecent. In spite of this, the dance, already known in the sixteenth century, gained in popularity in the following century, and it was incorporated into theatrical representations up to the first years of the eighteenth century.

— Manuel Pedro Ferreira

1. Juro te para San Gil etc. |

1. I swear by Saint Gil |

2. Crece s'estou na cidade, |

2. It grows if I am in town, |

4. |

4. |

5. Y su furioso zelo |

5. And their furious violence |

6. |

6. |

7. Para cuidados não mais

|

7. I chose no more cares Now that I feel in myself |

9. No tempo que mais folgava, |

9. At the time I made most merry, |

10. Quitaste sperança mia, |

10. You cut me from hope: |

14. Levay-me, amor, à ilha perdida, |

14. Take me, love, to the lost isle, |

16a. 16b. |

16a. 16b. |

18. Chorava uma alma devota, e por não querer queixar-se A causa de seus suspiros he seu amante ausentar-se Deixaste-me, meu querido, em tão tristes saudades! |

18. A devoted soul was crying, and in order not to complain, The cause of my sighs is the absence of my love; You left me, my love, in such sad longing! |

20. Canta Bacião, canta tu Thomé, Copla: Nacemo de hunsmay donzera huns Rey que mia Deuza he |

20. Sing, Bastian, you sing, Thomas, You go, Francisco, move your feet, Verse: There was born of a maiden a king who is my God. |

Listen Now

download

Subscribe (itunes)

Subscribe (rss)

help

Performers

Vozes Alfonsinas

The ensemble Vozes Alfonsinas, based in Lisbon, Portugal, has been active since June 1995. Its focus is Iberian music from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The repertory is largely based on original research by musicologist Manuel Pedro Ferreira, the group’s founder and artistic director. Vozes Alfonsinas has performed all over Portugal and also in Spain, Italy, Holland, and the United States. The group’s CD recordings include cantigas by Martin Codax (Xerais, 1998), other medieval songs under the title The Time of the Troubadours (Strauss/PortugalSom, 2000), villancicos from La Mar de la Musica (EMI-Classics, 2001), a selection of pieces from Visigothic times to the Renaissance, and chants from the rite of Braga (Arte das Musas/CESEM, 2008). Classics Today considered Time of the Troubadours “a fine bit of work, recommended for anyone interested in medieval music—or just looking for something very old and different.”

Plainsong and Medieval Music says of the most recent recordings: “The singing is of exquisite purity . . . the selection is well chosen and beautifully performed. Highlights include duet performances of some of the early polyphony. . . . The second CD is a much appreciated inclusion, [on account of] the beauty of the singing and the value of the disc as an aid to reimagining the medieval liturgical soundscape of one of Braga’s most important feasts.” Another CD, Mon Seul Plaisir, based on a fifteenth-century Italian manuscript now in Oporto, awaits an opportunity for publication.

Manuel Pedro Ferreira

Manuel Pedro Ferreira, artistic director of Vozes Alfonsinas, was born in 1959 in Lisbon, Portugal. He received his PhD from Princeton University in 1997 on the topic of Gregorian chant at Cluny. Since 2000 he has served on the faculty of the Music Sciences Department of Lisbon’s Universidade Nova. He is also executive director of the Music Sociology and Aesthetics Research Centre at the university.

Ferreira, an active member of scholarly boards in Brazil, Spain, Britain, and Belgium, is also a member of the Academia Europaea. He was recently elected to the Directive Board of the International Musicological Society. He has served as visiting professor at the Universidade Federal Fluminense (Brazil), at the Universidad de Granada (Spain), and at the École Pratique des Hautes Études (France). In addition to being a consultant for the Israel Science Foundation, the Research Foundation Flanders, and the University of Bologna, Ferreira led and managed musicology projects in Portugal and has participated in several others that were related to art and literature in Portugal and Spain.

Dedicated to the study of medieval culture, Ferreira has published numerous papers on early and contemporary Portuguese music. He is considered the leading expert on the music of the Galician-Portuguese cantigas, and as such he has been a consultant for the Centre for the Study of the Cantigas de Santa Maria (University of Oxford). He received the Music Essay Award from the Portuguese Music Council for his 1986 bilingual publication The Sound of Martim Codax and was responsible for the facsimile edition of both Cancioneiro da Biblioteca Publia Hortensia de Elvas (Lisbon, 1989) and the Porto 714 MS (Porto, 2001). He also wrote the monograph Cantus Coronatus: Seven cantigas d’amor by King Dinis (Kassel, 2005) and edited books on twentieth-century music and the Renaissance. Many of his most significant papers relating to the Middle Ages were issued in book form in Portugal (Iberian topics) and the UK (French topics).

Listen Now

download

Subscribe (itunes)

Subscribe (rss)

help

Related Images

Top: The ensemble Vozes Alfonsinas performs at the Freer Gallery’s Meyer Auditorium in 2007. (L-R): Maria Repas, soprano; Madalena Cabral, rebec; Susana Teixeira, mezzo-soprano; César Viana, recorders; Gonçalo Pinto Gonçalves, tenor; Nuno Torka Miranda, Renaissance guitar and vihuela; Vítor Gaspar, baritone; and André Barrosa, theorbo. Bottom: The ensemble performs for a family audience in the Sackler Gallery.

Madalena Cabral plays a rebec, an instrument derived from the Middle Eastern rabab. As it traveled along the Silk Road and other trade routes, the rabab assumed a variety of forms and became part of music cultures across Asia.

André Barrosa performs on a theorbo, a long-necked lute used as a bass instrument in ensembles, for solo parts, and to accompany opera. It essentially disappeared from use by the time of Mozart in the eighteenth century, but it was rediscovered in the late nineteenth century during a revival of early music in Europe and North America.

A revival of interest in early European music occurred in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The American artist Thomas Dewing created this painting of a woman with a theorbo around 1904. Dewing acquired the antique instrument from the renowned architect Stanford White.

Girl with Lute, by Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851–1938). Oil on wood panel, 1904–1905. Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1905.2.

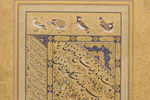

Europeans artists and missionaries traveling to Asia in the sixteenth century promoted Western ideas of religion and art. Some of the artwork created during the Mughal Empire (in present-day India) confirms the emperor’s interest in Roman Catholic imagery and European styles of representation, as seen in the border of this Islamic folio.

Folio from the Gulshan (Rose Garden) Album. India, Mughal dynasty, ca. 1600. Calligraphy by Mir Ali al-Katib (Bukhara, ca. 1540). Opaque watercolor, gold, and ink on paper. Purchase, F1956.12.

These figures from the border of an Islamic folio created in India about the year 1600 depict St. Anthony (left), Christ and the Ship of Salvation, God the Father (upper right), and the Virgin Mary with the Christ Child and St. John.

Details, folio from the Gulshan (Rose Garden) Album. India, Mughal dynasty, ca. 1600. Calligraphy by Mir Ali al-Katib (Bukhara, ca. 1540). Opaque watercolor, gold, and ink on paper. Purchase, F1956.12.

During the sixteenth century, when most of the music on this podcast was composed, European priests traveled to Japan as missionaries. Here, missionaries in Nagasaki show reverence before a sacred image. From the mid-1500s until 1639, missionaries from Portugal, Spain, and Italy accompanied European traders as they shipped goods from China to Japan.

Detail, Southern Barbarians in Japan. Japan, Edo period, 17th century. One of a pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, and gold on paper. Purchase, F1965.22–23.

Listen Now

download

Subscribe (itunes)

Subscribe (rss)

help

The Credits

This podcast is coordinated by Michael Wilpers, public programs manager.

It was made possible through support from the Thaw Charitable Trust. Audio preservation and editing of this recording were supported by funds from the Smithsonian Women’s Committee.

Thanks to Andy Finch for audio recording, SuMo Productions for audio editing, Neil Greentree and John Tsantes for photography, Nancy Eickel for text editing, Torie Castiello Ketcham for web design, Betsy Kohut and Cory Grace for artwork images, and especially the artists for permission to present this performance as a podcast.

Podcast Series

Concerts

Storytelling

Lectures

Subscribe to this Series

RSS

RSS iTunes

iTunes

About Podcasts

About podcasting and how to get started

![]() Tell us what you think

Tell us what you think

Radio Asia

Explore music from all across Asia with Radio Asia, a stream of complete tracks from the collections of Smithsonian Global Sound

Most Recent Podcasts

Musicians from Marlboro IMusic of Toru Takemitsu and Tan Dun: Ralph Van Raat, piano

The Legacy of Yatsuhashi

The Traveler’s Ear: Scenes from Music

Western Music in Meiji Japan: Gilles Vonsattel, piano

Western Music in Meiji Japan

The Art of Afghan Music

Painting with Music: Bell Yung, qin

Sounds from Arabia

Tarek Yamani Trio