Yogic Identities: Tradition and Transformation

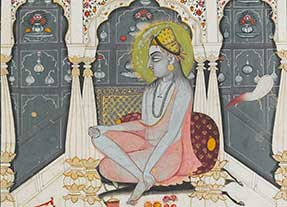

The earliest textual descriptions of yogic techniques date to the last few centuries BCE and show their practitioners to have been ascetics who had turned their backs on ordinary society.1 These renouncers have been considered practitioners of yoga par excellence throughout Indian history. While ascetics, including some seated in meditative yoga postures,2 have been represented in Indian statuary3 since that early period, the first detailed depictions of Indian ascetics are not found until circa 1560 in paintings produced under the patronage of Mughal Emperor Akbar (reigned 1556–1605) and his successors.4 These wonderfully naturalistic and precise images illuminate not only Mughal manuscripts5 and albums but also our understanding of the history of yogis6 and their sects. Scholars have argued for these paintings’ value as historical documents;7 their usefulness in establishing the history of Indian ascetic orders bears this out. The consistency of their depictions and the astonishing detail they reveal allow us to flesh out—and, sometimes, rewrite—the incomplete and partisan history that can be surmised from Sanskrit and vernacular texts, travelers’ reports, hagiography, and ethnography.8

The earliest textual descriptions of yogic techniques date to the last few centuries BCE and show their practitioners to have been ascetics who had turned their backs on ordinary society.1 These renouncers have been considered practitioners of yoga par excellence throughout Indian history. While ascetics, including some seated in meditative yoga postures,2 have been represented in Indian statuary3 since that early period, the first detailed depictions of Indian ascetics are not found until circa 1560 in paintings produced under the patronage of Mughal Emperor Akbar (reigned 1556–1605) and his successors.4 These wonderfully naturalistic and precise images illuminate not only Mughal manuscripts5 and albums but also our understanding of the history of yogis6 and their sects. Scholars have argued for these paintings’ value as historical documents;7 their usefulness in establishing the history of Indian ascetic orders bears this out. The consistency of their depictions and the astonishing detail they reveal allow us to flesh out—and, sometimes, rewrite—the incomplete and partisan history that can be surmised from Sanskrit and vernacular texts, travelers’ reports, hagiography, and ethnography.8

The Two Yogi Traditions: Ascetic Saṃnyāsīs and Tantric Nāths

The eleventh to the fifteenth centuries saw the composition of a corpus of Sanskrit works that teach the haṭha method of yoga, which places the greatest emphasis on physical practices.9 The techniques of haṭha yoga—some of which were probably part of ascetic practice for more than a thousand years before they were taught in texts—became integral to subsequent formulations of yoga, including orthodox ones such as those found in the later “Yoga Upaniṣads.”10 They form the basis of much of the yoga practiced around the world today.

Within the texts of the haṭha yoga corpus, we can identify two yogic paradigms. One, the older, is the tradition of the yogis described in our earliest sources and is linked to the physical practices of tapas—asceticism. It uses a variety of physical methods to control the breath and to arrest the downward flow and loss of semen,11 which is said to be the essence of life. Control of breath and semen leads to control of the mind, as well as perfect health and longevity. In classical formulations of haṭhayoga—such as that found in the most influential text on the subject, the fifteenth-century Haṭhapradīpikā—a second paradigm, that of Tantric yoga, is superimposed onto this ancient ascetic method. As taught in its root texts, which were composed between the fifth and tenth centuries CE, Tantric yoga consists for the most part of meditations on a series of progressively more subtle elements, a progression represented in some Kaula Tantric texts from the tenth century onward by the visualization of the ascent of the serpent goddess Kuṇḍalinī through a series of wheels (cakras) or lotuses (padmas) located along the body’s central column.

The ultimate goal of both of these yogic paradigms is liberation (mokṣa), which can be achieved while alive. Along the way various supernatural abilities or siddhis are said to arise, ranging from mundane benefits such as overcoming hunger and thirst through the power of flight to the attainment of an immortal body. In the ancient ascetic tradition, these siddhis are ultimately impediments to the final goal; in the Tantric tradition, they may be ends in themselves.12

This mixing of yogic traditions suggests an ascetic milieu in which techniques were exchanged freely, a suggestion corroborated by the lack of emphasis on sectarianism in the texts of the early haṭhayoga corpus. The earliest text to teach a yoga explicitly called haṭha declares: “Whether a Brahmin, an ascetic, a Buddhist, a Jain, a Skull-Bearer or a materialist, the wise one who is endowed with faith and constantly devoted to the practice of [haṭha] yoga will attain complete success.”13

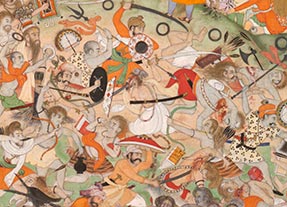

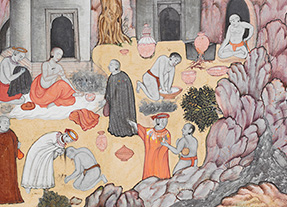

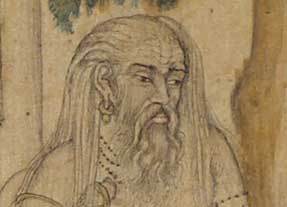

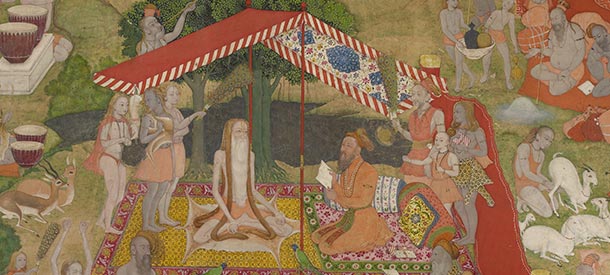

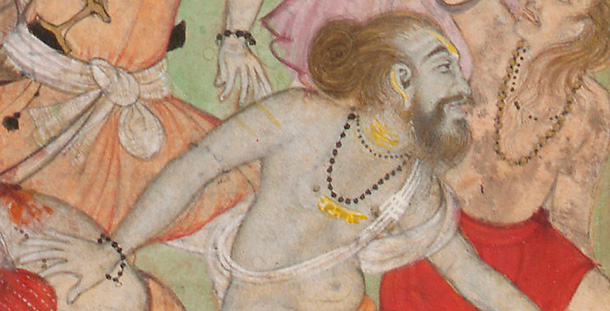

Early Mughal paintings bear witness to an ascetic archetype. Yogis have long, matted hair and beards, are naked or nearly so—what cloth they do wear is ochre-colored—and smear their bodies with ashes. In addition to these long-attested ascetic attributes, Mughal-era yogis display some more recent traits: they wear hooped earrings,14 sit around smoldering fires,15 and drink suspensions of cannabis.16 See, for example, some of the finest early Mughal depictions of Indian yogis—a single folio from the St. Petersburg Muraqqa‘ (Album), which shows a camp of ascetics (fig. 1) or two folios from a manuscript of the Akbarnāma showing a battle between two Saṃnyāsī suborders (figs. 2 and 3).

Figure 1. View full & caption | View in new window

But although the two yogi traditions clearly interacted, sharing both theory and practice, their lineages remained distinct.17 They were represented, in the case of the ancient tradition of celibate asceticism, by groups that today constitute sections of the Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsī and Rāmānandī ascetic orders, and, in the case of the tradition of Tantric adepts such as Matsyendra and Gorakṣa,18 by groups that today constitute sections of an ascetic order now known as the Nāths.19 These orders were only starting to be formalized in the early Mughal period.20 Today they remain, together with the Sikh-affiliated Udāsins, the biggest ascetic orders in North India.

Figure 4. View full & caption | View in new window

Naked Saṃnyāsīs and Nāths with Horns

We know from external evidence that the ascetics depicted fighting in two folios (figs. 2, 3) from the Akbarnāma (1590–95) and those depicted in two folios (figs. 7, 8) from the Bāburnāma are from lineages belonging to the two separate yogi traditions.

Figures 2 and 3 depict a battle, witnessed by Emperor Akbar, that took place in 1567 on the banks of the bathing tank at Kurukshetra. The combatants belonged to two rival yogi suborders, and they were fighting over who should occupy the best place to collect alms at a festival. In his description of the battle, Akbarnāma author Abu’l Fazl called the combatants Purīs and Giris, which remain to this day two of the “ten names” of the Daśanāmī or “Ten-Named” Saṃnyāsīs.21

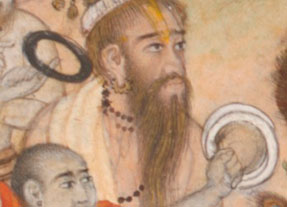

Figures 7 and 8 are illustrations from a circa 1590 manuscript of the Bāburnāma and depict a visit Emperor Bābur made in 1519 to a monastery at Gurkhattri in modern-day Peshawar, Pakistan. The manuscript and its illustrations were made under the patronage of Akbar, who himself visited Gurkhattri twice in 1581,22 so the illustrations are likely to depict the monastery and its inhabitants at that time.23 Until the partition of India, Gurkhattri was an important center of the Nāth ascetic order,24 and there is still a temple to Gorakṣa, its founder, at the site today.25 This does not confirm that Gurkhattri was in the possession of Nāths at the time of either Bābur’s or Akbar’s visit—many such shrines have changed hands over time—and the inhabitants of Gurkhattri are not identified in the Bāburnāma as Nāths, but rather as jogī(s),26 a vernacular form of the Sanskrit yogī, which can refer to ascetics of a variety of traditions. However, we can infer that they were Nāths27 from three attributes that they do not share with the Saṃnyāsīs shown fighting at Kurukshetra in the Akbarnāma.

The first is the wearing of horns on threads around their necks. Today, the single most reliable indicator of Nāth membership is the wearing of such horns (see fig. 11).28 Nāths now call their horns nāds, but they were formerly known as siṅgīs, and this appears to have been the case in the medieval period. In medieval Hindi literature siṅgīs are frequently mentioned among the accoutrements of yogis, and siṅgī-wearing yogis are sometimes identified as followers of Gorakṣa.29 In keeping with their lack of sectarianism, Sanskrit texts on haṭha yoga, even those associated with Gorakṣa, make few mentions of sect-specific insignia, and none of siṅgīs, but other Sanskrit sources associate yogi followers of Gorakṣa with the wearing of horns. Thus an early sixteenth-century South Indian Sanskrit drama describes a Kāpālika ascetic as uttering “Gorakṣa, Gorakṣa” and blowing a horn,30 and the tenth chapter of a Sanskrit narrative from Bengal dated to the second half of the sixteenth century or earlier31 tells of the yogi Candranātha being awoken from his meditation by other yogis blowing their horns.32 From the fourteenth to the sixteenth century travelers to the regions in which the earliest references to Gorakṣa are found33 reported the use of horns by yogis.34 The identification of ascetics who wear horns as Nāths is supported by a painting of the annual Urs festival of Mu’inuddin Chishti at Ajmer completed in the 1650s35 and now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.36 At the bottom is a group of Hindu ascetics. The fourth and fifth figures from the right, who both sport siṅgīs, are identified on the painting itself as Matsyendra and Gorakṣa, the first human Nāth gurus.

The other two specifically Nāth attributes are the necklace and fillet worn by three of the ascetics in figure 8. At the end of the sixteenth century the Jesuit traveler Monserrate visited Bālnāth Ṭillā, a famous Nāth shrine in the Jhelum district of Pakistani Punjab, which was the headquarters of the order until the partition of India.37 Describing the monastic inhabitants of the Ṭillā, Monserrate wrote, “The mark of [the] leader’s rank is a fillet; round this are loosely wrapped bands of silk, which hang down and move to and fro. There are three or four of these bands.”38 This description seems to conflate two items of apparel often depicted in Mughal paintings of yogis: a simple fillet and a necklace, hanging from which are colored strips of cloth (Monserrate’s silk bands).39 Neither of these is worn today,40 but they serve to identify their wearers in Mughal paintings as Nāth yogis.41

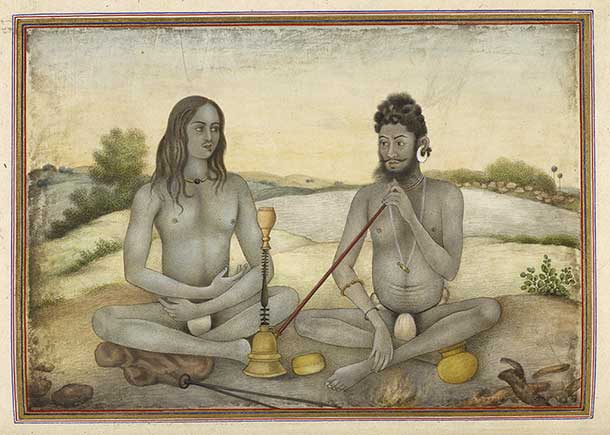

These indicators of membership of the Nāth order—the horns, fillets, and necklaces—enable us to identify ascetics in a large number of early Mughal paintings, including those depicted in this beautiful seventeenth-century painting of yogis (fig. 9), as Nāths.42

Figure 9. View full & caption | View in new window

Once members of the Nāth saṃpradāya have been identified, it is possible to note other attributes that Nāths do not share with the Saṃnyāsīs depicted in contemporaneous illustrations. These include the wearing of cloaks and hats, the accompaniment of dogs, and the use of small shovels for moving ash. The Saṃnyāsīs, meanwhile, in keeping with the renunciation implied by their name, do relatively little to embellish their archetypal ascetic attributes and are thus best distinguished by the absence of the specifically Nāth features noted above.43 Indeed, in some cases, their renunciation is such that they are naked, which the Nāths never are. Figure 1, then, shows a Saṃnyāsī encampment.

There are fewer Mughal pictures of Saṃnyāsīs than of Nāths.44 The north Indian ascetic Nāth traditions encountered by the Mughals were closely linked to the Sant tradition of holy men and, like them, believed in a formless, unconditioned god. This theological openness—which manifested in, among other things, a disdain for the purity laws adhered to by more orthodox Hindu ascetics—allowed them to mix freely with those such as the Muslim Mughals, who more caste-bound Hindu traditions would consider mlecchas (barbarians).45 Furthermore the Nāths were not militarized, unlike the Saṃnyāsīs, whose belligerence would have proved an impediment to interaction with the Mughals.46 The Nāths’ greater influence on the Mughal court is further borne out by the preponderance of their doctrines in Persian yoga texts produced during the Mughal period.47

Earrings

The criteria used above to identify the Nāths and Saṃnyāsīs in early Mughal paintings have been taken exclusively from sources contemporaneous with or older than the paintings themselves. This is because using modern ethnographic data to interpret these images has its pitfalls. By now the reader acquainted with the Nāths may have wondered why little mention has been made of earrings. Today, Nāths are renowned for wearing hooped earrings through the cartilages of their ears, which are cut open with a dagger at the time of initiation.48

Figure 10. View full & caption | View in new window

For this reason, they are sometimes referred to as kānphaṭā (split-eared), a pejorative term that they themselves eschew. Very few other ascetics today wear earrings of any sort and, to my knowledge, none wears them kānphaṭā-style.49 The current exclusive association of Nāths wearing hooped earrings has led many scholars to take textual mentions or artistic depictions of such insignia as indications that the wearers are Nāths, but this is not always the case. In India, earrings have long been emblematic of both divinity50 and rank.51 Thus many representations of the Buddha show him with earlobes that are distended and pierced but empty, signifying his renunciation: he had abandoned the heavy jeweled earrings he wore as a royal prince.52 In contrast, Mahāyāna bodhisattvas and Tantric adepts (siddhas) were conceived of as sovereigns of their realms and are often described and depicted as wearing earrings (and other regal accoutrements).53 These Hindu and Buddhist siddhas may have been the first ascetics to wear earrings; a related type of ascetic, the Kāpālika (Skull bearer), is often said to wear them.54

In medieval vernacular texts contemporaneous with early Mughal paintings, earrings are almost always included (usually as mudrā) in lists of yogi insignia.55 Often they are associated with yogis who follow Gorakṣa. If we look at the ears in figures 1–3 and 7–9, however, we see two surprising features. First, almost all, whether they belong to Nāths or Saṃnyāsīs, sport earrings. Second, no earring goes through cartilage. Depictions of Saṃnyāsīs up to the eighteenth century often show them wearing earrings, and it is not until the late eighteenth or even early nineteenth century that we come across the first depictions of Nāths wearing earrings kānphaṭā-style. A fine example is a painting of two ascetics that illustrates a manuscript of the Tashrīḥ al-aḳvām, an account of various Indian sects, castes, and tribes commissioned by Colonel James Skinner and completed in 1825 (fig. 11). The ascetic on the left is identified in an expanded version of the picture from the same period as an Aughaṛ, i.e., a Nāth who is yet to take full initiation; the one on the right, who wears a siṅgī around his neck and kānphaṭā earrings, is a full initiate by the name of Śambhu Nāth.56

Travelers from the sixteenth century onward commented on the wearing of earrings by yogis,57 but there are no outsider reports of them being worn kānphaṭā-style until circa 1800.58 The seventeenth-century poet Sundardās, whose earliest manuscript is dated 1684,59 contrasts earring-wearing jogīs with jaṭā-growing Saṃnyāsīs (pad 135) and elsewhere derides splitting the ears (kān pharāi) as a means of attaining yoga (sākhī 16.23).60 Since no paintings of yogis from the Mughal heyday (up to 1640) show split-eared yogis, it thus seems likely that the practice developed in the second half of the seventeenth century. The use of the pejorative name kānphaṭā, however, is not found until the second half of the eighteenth century, suggesting that the practice did not become widespread until then. The Nāths’ adoption of this extreme kānphaṭā style led to earrings in general being closely associated with the Nāth order, with the result that other ascetic orders eschewed the practice.61

Figure 11. View full & caption | View in new window

The received history of the Nāths is based on hagiography and has the twelfth-century Gorakṣa founding the order, complete with its twelve subdivisions, by putting earrings through the cartilages of his disciples’ ears. The order is said to have flourished until the eighteenth century or thereabouts and to have been in steady decline ever since. But close examination of the historical sources shows that the opposite is more likely.62 The first organization to claim authority over all Nāth lineages was founded in 1906.63 The Nāth saṃpradāya (Nāth order) often referred to in histories of yoga and yogis was in fact a variety of disparate orders that traced their lineages to one or another Tantric siddha. Thus Jālandharnāth was the tutelary deity of Maharaja Man Singh’s Jodhpur in the early nineteenth century, and Gorakṣa played a subsidiary role in the texts and paintings produced at Man Singh’s court64 until late in his reign (1803–43).65 The adoption of kānphaṭā-style earrings appears to have been part of the process of Gorakṣa’s becoming the titular head of the order and is always associated with Gorakṣa in legend.66 The earliest image of Jālandharnāth from Man Singh’s reign, a painting of him at his seat in Jalore, shows him and his attendants wearing earrings in their earlobes (fig. 12).67 In subsequent depictions of Nāths from the region, such as another of Jālandharnāth in a folio from the Nāth Carit (fig. 13), they sport kānphaṭā-style earrings.68 The Nāth Carit identifies the previously preeminent Jālandharnāth with Gorakṣa.69 Jālandharnāth was also identified with the Bālnāth of Bālnāth Ṭillā, which, as noted above, was known as Gorakh Ṭillā by the second half of the eighteenth century.70

Just as the Nāths’ earrings changed as the result of changes in the Nāth saṃpradāya, so too did their horns. The siṅgī worn by Nāths today is a more complex affair than that depicted in Mughal painting, which appears to have been an antelope horn eight to ten centimeters long, worn on a short thread around the neck so that it rested on the upper part of the chest. Today’s siṅgī ensemble consists of a stylized miniature horn—more of a whistle—about three centimeters long and one centimeter in diameter, which is made from a variety of different materials, ranging from gold to plastic. It is worn around the neck with a ring (pāvitrī) and a rudrākṣa (Elaeocarpus ganitrus Roxb.) seed on a long thread of spun black wool that hangs almost to the waist.

Figure 14. View full & caption | View in new window

The Nāths call this ensemble either a selī or a janeo (fig. 14). The latter is a Hindi word for the yajñopavīta or “sacred thread” worn by twice-born Hindus, and suggests a clue to the changes in Nāth neckwear.

The watershed in the Nāths’ siṅgī configuration can be seen in paintings from Man Singh’s reign in Jodhpur. Figure 12 has Jālandharnāth and his companions wearing their stylized siṅgīs on short threads around their necks, without a ring or rudrākṣa seed, in the manner of those shown in figures 7, 8, and 9. Once the “mature archetype” of Jālandharnāth was established,71 he and his companions were always shown wearing their siṅgīs (without a ring or rudrākṣa seed) on waist-length black threads, usually around their necks (in the same manner as the yogi in fig. 11) but sometimes over one shoulder and under the other in the manner of a brahmin’s sacred thread.72 It seems that the newer, longer ensemble came about in imitation of the brahmanical janeo. During their heyday, the Jodhpur Nāth householders “began to adopt high-caste Hindu ways,”73 and we see in texts commissioned by Man Singh an alignment between the previously unorthodox Nāth tradition and classical Hinduism.74

Yogi Followers of Śiva and Viṣṇu

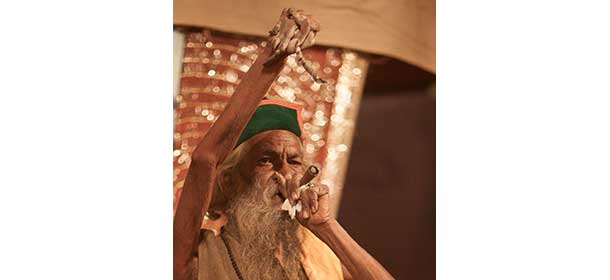

The most significant fault line in Hindu theology is the division between Śaivas, who hold that the supreme being is Śiva or his consort, Devī, and Vaiṣṇavas, who hold that it is Viṣṇu or one of his incarnations (avatāras), usually Rāma or Kṛṣṇa. This division was at its most violent in the eighteenth century, when battles between the military wings of two yogi orders, the Śaiva Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsīs and Vaiṣṇava Vairāgīs (whose largest suborder is that of the Rāmānandīs), resulted in the deaths of thousands of ascetics. To this day, the sādhu camps at the triennial Kumbh Melā festivals are divided into the army of Śiva and the army of Rām (fig. 15). Mughal-era paintings of ascetics, however, show that the situation was somewhat different in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as we shall see below.

Figure 15. View full & caption | View in new window

Nowadays the Nāths, like the Saṃnyāsīs, are overtly Śaiva, but the pictorial record indicates that this has not always been the case: Nāths are not shown sporting Śaiva insignia, such as rudrākṣa seeds or tripuṇḍras (horizontal forehead markings made with ash) until the late eighteenth century.75 The current Nāth janeo configuration, in which a ring and a rudrākṣa seed have been added to the long black thread and siṅgī, appears to be an innovation of the nineteenth century at the earliest.76 The Nāths’ roots in Śaiva Tantric traditions make the absence of Śaiva insignia in Mughal depictions of them surprising; perhaps it is symptomatic of their devotion to a formless absolute, an attitude prevalent in North Indian ascetic orders in late medieval India.77

But it is not only the Nāths who are free from Śaiva insignia in Mughal paintings; to my knowledge, no ascetic of any stripe wears the horizontal tripuṇḍra forehead marking or necklaces of rudrākṣa seeds. The unmistakable Śaiva denomination of today’s Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsīs makes the absence of Śaiva insignia in their Mughal depictions particularly surprising. In myths, Śiva is often portrayed as the yogi par excellence, with the result that asceticism and yoga have come to be thought of as originally Śaiva, and their non-Śaiva manifestations as adaptations of Śaiva traditions. But in our earliest sources, the association of asceticism and yoga with Śiva is by no means exclusive,78 and Śaivism did not dominate subsequent teachings on yoga.79 It is perhaps the association of asceticism with Śiva and the Śaiva affiliation of today’s Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsīs that have led scholars to assume that the ascetics in Mughal paintings are Śaivas.80 Yet, as I have remarked, there are no Śaiva insignia in any Mughal pictures of ascetics.81 On the contrary, many of the Saṃnyāsīs depicted therein sport on their foreheads the distinctive ūrdhvapuṇḍra V-shaped Vaiṣṇava marking. A large number of the Saṃnyāsīs fighting in figures 2 and 3 clearly have these markings (see details in 16b, 16c, 16d), as does the leader of the Saṃnyāsī troop (figs. 1, 16a). Other Mughal paintings of Saṃnyāsīs from the same period also show them wearing ūrdhvapuṇḍras (e.g. figures 18 and 19).82

Vaiṣṇava features of Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsī identity are in fact legion. To this day, all Daśanāmī ascetics greet one another with the ancient Vaiṣṇava aṣṭākṣara (“eight-syllabled” mantra): oṃ namo nārāyaṇāya. Śaṅkarācārya, who was retroactively claimed to have founded their order, was Vaiṣṇava.83 Three of their four pīṭhas or sacred centers—Dwarka, Puri, and Badrinath—are Vaiṣṇava places of pilgrimage.84 Prior to the sixteenth century, the Daśanāmī nominal suffix Purī is found only on the names of Vaiṣṇava ascetics.85 The tutelary deities of the two biggest akhāṛās (regiments) of the Daśanāmīs today are Dattātreya and Kapila, both of whom are included in early lists of the manifestations of Viṣṇu.86

It is the ūrdhvapuṇḍras in these Mughal miniatures, however, and the absence of Śaiva insignia that provide us with the most compelling evidence that at least some of the groups that came to form the Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsī order were originally Vaiṣṇava. It is not clear how, when, or why the Daśanāmīs acquired an overarching Śaiva orientation, but it is likely to have been a result of the formalization of the order, in particular its affiliation with the southern Sringeri monastery and the concomitant attribution of its founding to Śaṅkarācārya, who by the seventeenth century had been rebranded a Śaiva.87 During the seventeenth century, the three main ascetic orders of North India—the Daśanāmīs, Rāmānandīs, and Nāths—forged links with southern institutions as they staked claims to dominion over all of India. The Daśanāmīs joined forces with the Sringeri maṭha, whose teachings, a blend of Advaita and the sanitized form of Śaivism known as Śrīvidyā, they adopted.88 As part of this process, both the Sringeri maṭha and the Daśanāmīs claimed Śaṅkarācārya as their founding guru. Together with Śaivism, the Daśanāmīs would have taken northward the antipathy between Śaivas and Vaiṣṇavas that had afflicted South India for at least five hundred years. It persisted in debates between different Brahmin and Saṃnyāsī factions, some of which were connected with the Sringeri maṭha, in Vijayanagar until its downfall in 1565 and, latterly, in Varanasi.89

The rapid hardening of the Daśanāmīs’ Śaiva orientation over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was likely to have been in reaction to the formation of their archrivals, the Rāmānandīs, ascetic worshipers of Viṣṇu’s Rām incarnation. Today, Rāmānandīs wear Vaiṣṇava ūrdhvapuṇḍra forehead markings like those depicted in the early Mughal portrayals of Saṃnyāsīs (figs. 17, 18, 19).

Figure 17. View full & caption | View in new window

Indeed, one might contend that figure 1—whose subjects, unlike those in figures 2 and 3, are not identified in contemporaneous sources as Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsīs—portrays Rāmānandīs (or rather their forerunners, since the order was yet to be formalized or refer to itself as Rāmānandī).90 But three features of the ascetics in figure 1 set them apart from today’s Rāmānandīs.

First, there is the ancient ūrdhvabāhu penance of permanently holding one or two arms in the air undertaken by the ascetic in the bottom left of the picture. Today this is the preserve of Daśanāmīs (fig. 20).

Figure 20. View full & caption | View in new window

Rāmānandīs will not practice it because it is likely to permanently disfigure the body, rendering it unsuitable for the orthodox Vedic ritual acts that they, unlike the Saṃnyāsīs, perform (fig. 21).

Figure 21. View full & caption | View in new window

Rāmānandīs prefer austerities such as dhūni-tap, sitting in the summer sun surrounded by smoldering cow-dung fires (fig. 22), or khaṛeśvarī, standing up for years on end (fig. 23).

Second, two of the ascetics, including the figure who has undertaken the ūrdhvabāhu penance, are naked. Rāmānandīs today are scornful of the Daśanāmīs’ nakedness, saying that it offends Lord Rām.91 Third, the remaining ascetics wear ochre-colored cloth, unlike the Rāmānandīs, who wear white cloth, saying that the Daśanāmīs’ ochre robes are the color of the menstrual fluid of Pārvatī, Śiva’s consort.92

Other features differentiate the Rāmānandīs from the Daśanāmīs, such as the former’s insistence on “pure” (i.e., lacking onion and garlic) vegetarian food, their taking of the nominal suffix -dāsa at initiation, their practice of orthodox rituals, and the associated preservation of the topknot when they have their heads shaved at initiatory and other ceremonies. These differences are all emblematic of the Rāmānandīs’ ultra-Vaiṣṇavism, a trait shared with other members of the “four traditions” (cār saṃpradāya) of Vaiṣṇavas, which were formalized in the seventeenth century and sought to unite North Indian devotional traditions with more established South Indian lineages.93

If one puts these ultra-Vaiṣṇava traits aside, however, the Daśanāmīs and Rāmānandīs are remarkably similar, and not just because they both embody a shared ascetic archetype and lead almost identical lives. Their organization and initiation procedures are very close.94 They both worship Hanumān and gods and sages associated with the ancient ascetic yoga tradition, such as Dattātreya and Kapila.95 They share a secret vocabulary.96 The nominal suffix -ānanda found in the names of early Rāmānandī gurus prior to the adoption of the suffix -dāsa is still used by certain subdivisions of the Daśanāmīs.97 Both have a military unit (akhāṛā) called (Mahā) nirvāṇi.

Today, the Rāmānandīs are the largest ascetic order in India, and ascetics who worship Rāma have been part of the North Indian religious landscape since at least the twelfth century.98 But our Mughal miniatures have shown us only Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsīs and Nāths. Where were the ascetic worshippers of Rāma hiding? A close inspection of Akbar Watches a Battle between Two Rival Groups of Saṃnyāsīs at Thaneshwar and a folio from Jahangir’s 1618 Gulshan Album tells us that they are right before our eyes: the forerunners of the Rāmānandīs were Saṃnyāsīs.99 Some of the yogi warriors in the Akbarnāma depiction of the battle at Thaneshwar have, in addition to Vaiṣṇava insignia, words written on their bodies. Only one word—ramā—is discernible, on the chest of a Saṃnyāsī in the bottom right (figs. 2, 24). And we can see similar markings on the body of a Vaiṣṇava in a beautiful collage of paintings from the Gulshan Album, which depicts a Nāth yogi encountering a Vaiṣṇava ascetic very similar to the Thaneshwar Saṃnyāsīs (fig. 25). The words are not clearly written—one wonders how good the Devanāgarī orthography of the Mughal court painters was—but rāma is the most likely reading.

Figure 24. View full & caption | View in new window

In matters of doctrine, the Saṃnyāsī tradition is most closely associated with the rigorous philosophies of Vedānta. Bhakti (devotion), however, has held an important, if overlooked, place in their teachings,100 and some medieval North Indian Saṃnyāsī ācāryas were renowned for their devotion to Rām.101 The formalization of the Saṃnyāsī order involved the incorporation of a broad variety of different renouncer traditions, whose followers considered themselves part of the ancient tradition of renunciation (saṃnyāsa). In the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the generic name for a renouncer, Saṃnyāsī, became associated with this formalized order. When the Rāmānandīs seceded from it in the course of their adoption of ultra-Vaiṣṇavism, their ascetics differentiated themselves from the Saṃnyāsīs by giving themselves the name Tyāgī, which is an exact Sanskrit synonym of Saṃnyāsī (fig. 26). In a similar fashion, as Nāth corporate identity solidified in the eighteenth century, the name Yogī came to be associated exclusively with the Nāths and was shunned by the Saṃnyāsīs and Rāmānandīs.

The Śaivism of the Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsīs and Vaiṣṇavism of the Rāmānandīs, while ostensibly responsible for a lengthy, and sometimes lethal, antipathy, should be taken with a pinch of salt. Doctrinal differences are highlighted in texts composed by the learned of both traditions but, as noted above, the rank-and-file yogis were (and remain) very similar, and their shared Sant heritage of anti-scholastic nirguṇabhakti is still prevalent today. The Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava denominations were adopted in the course of the consolidation of the two orders and provided a convenient ideological justification for what was in fact competition over resources rather than a dispute over doctrine.102 Not only do the ascetics of both orders lead very similar lives, but many features of the two orders fly in the face of their supposed incompatibility. An important Saṃnyāsī commander of the late eighteenth century, when battles between the two orders were at their fiercest, was called Rāmānand Gosāīṃ.103 At the 2010 Haridwar Kumbh Melā, I met a Saṃnyāsī called Rāmānand Giri in the Saṃnyāsīs’ Jūnā Akhāṛā. Recently, when making inquiries in Himachal Pradesh about historical religious affiliations, my informants were confused by my attempts to categorize local rulers or religious institutions as exclusively Vaiṣṇava or Śaiva. Taruṇ Dās Mahant, a householder Rāmānandī from Kullu, told me that “here the devotees of Rām all worship Śiva and the devotees of Śiva all worship Rām.”104

Mughal Painting: A Window onto the History of Yoga and Yogis

There has long been confusion over the identity of the yogis depicted in Mughal and later paintings. This has resulted from a lack of understanding of the complex and constantly changing makeup of yogi sects in the early modern period, and the concomitant absence of terminological rigor in both Indian and foreign descriptions of yogis from the Mughal period to the present day. Yet a close reading of these pictures and other historical sources allows us to identify the sectarian affiliations of the depicted yogis and thereby to cast new light on their history and the nature of the yoga that they practiced. The pictures’ naturalism and the associated consistency of their depictions mean that seemingly insignificant details, such as the position of an earring, are of great significance.

Mughal-era and later paintings provide evidence for, and have inspired, many of the new ways of looking at Indian yogis and their history outlined in this essay. Doubtless some of the theories proposed will be rejected or refined in the light of further research—whether textual, ethnographic, or art historical—but the details shown in these beautiful images, which have hitherto been overlooked in histories of yoga and yogis, need to be addressed by historians. They bear testament to the fluidity of India’s religious landscape and the transformations undergone by her yogis as they adapted to the changes around them.

Author’s Note

I am grateful to Debra Diamond, Jane Lusaka, Bruce Wannell, Monika Horstmann, Arik Moran, Susan Stronge, Patton Burchett, Lubomír Ondračka, Anand Venkatkrishnan, Dominic Goodall, Jason Birch, Jerry Losty, Sunil Sharma, Péter-Dániel Szántó, Véronique Bouillier and Holly Shaffer for their useful comments on earlier drafts of this essay. Many of the arguments rehearsed had their first airing in a Mellon Foundation lecture I gave at Columbia University on September 29, 2011, at the kind invitation of Sheldon Pollock. I thank him and the audience there for their constructive criticism. I also received useful feedback from the members of the panel on “Yogis, sufis, devotees: religious/literary encounters in pre-modern and modern South Asia” at the European Conference on South Asian Studies in Lisbon, July 27, 2012. Many people have provided me with scans of images of yogis that I refer to in this essay. I would like to thank in particular Debra Diamond, who has sent hundreds of such scans my way. Ludwig Habighorst very kindly allowed me to use scans of pictures from his collection. Thanks too to Malini Roy, who has helped with my repeated requests to see images in the collection of the British Library.

Notes

1. E.g., the śramaṇa ascetics whose yogic practices the Buddha dismisses in the Pali Canon (see James Mallinson, “Śāktism and Haṭhayoga,” in The Śākta Traditions [London: Routledge, forthcoming]) and the practitioners of yoga mentioned in the Mahābhārata (ibid., and John L. Brockington, “Epic Yoga,” Journal of Vaiṣṇava Studies 14, no. 1 [2005], pp. 123–38).

2. On the history of yoga postures (āsanas) and their depiction, see cats. 9a–j, Asana, in Yoga: The Art of Transformation, ed. Debra Diamond (Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 2013).

3. The earliest depictions of yogis in yogic postures date to approximately the third century BCE (see n. 5 in cats. 9a–j, Asana, in Yoga: The Art of Transformation). Ever since Sir John Marshall’s identification of the figure depicted on a seal from Mohenjo-Daro as a third-millennium BCE prototype of Śiva in a yogic posture, many scholars have claimed that yoga was practiced in the Indus Valley Civilization. Sir John Marshall, Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization: Being an Official Account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro Carried Out by the Government of India Between the Years 1922 and 1927, vol. 1 (London: Arthur Probsthain, 1931), pp. 52–54. In my opinion the absence of any textual or iconographic evidence for yogic postures over the subsequent two millennia (let alone the uncertainty over what the seal actually depicts) strongly suggests that there is no connection between the Indus Valley depictions and yoga (see also David Gordon White, Sinister Yogis (London: Chicago University Press) pp. 48-59)).

4. A large number of paintings of yogis were produced under the patronage of the Mughal courts, but very few depict yogis actually practicing yoga, whether in meditational or nonseated āsanas. Exceptions include the beautiful illustrations to manuscripts of the Baḥr al-Ḥayāt and Yogavāsiṣṭha, both in the collection of the Chester Beatty Library (mss. 16 and 5, respectively; see also cats. 9a–j and 13 in Yoga: The Art of Transformation). See Sunil Sharma, “The Sati and the Yogi: Safavid and Mughal Imperial Self-Representation in Two Album Pages,” In Harmony: The Norma Jean Calderwood Collection of Islamic Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), p. 154, shows how Mughal pictures of yogis were tools of propaganda in a broader scheme that “promoted the idea within and outside the empire of a tolerant and benevolent rule.”

5. Manuscripts of texts, in particular Premākhyān romances such as the Mrigāvatī, and individual verses describing a semi-spiritual longing for a beloved envisaged as a yogi are sometimes illustrated with paintings of yogis. These tend to portray generic yogi types, but still remain highly naturalistic, while other Mughal paintings depict specific individuals in a more ethnographic manner (cf. Sunil Sharma, “Representation of Social Groups in Mughal Art and Literature: Ethnography or Trope?” in Indo-Muslim Cultures in Transition [Leiden: Brill, 2011], pp. 22–30). More stylized still are the portrayals of yoginis in Deccani miniatures of the period, who, with their unlikely mixture of courtly apparel and ascetic garb, are likely to represent divine rather than human yoginis (Debra Diamond, “Occult Science and Bijapur’s Yoginis,” in Indian Painting: Themes, History and Interpretations [Essays in Honour of B. N. Goswamy], forthcoming 2013).

6. In this essay, I use the word yogi with the same lack of specificity that it has in many historical sources, both within the yogi tradition and without. Thus it refers to an ascetic—someone who has renounced the norms of conventional society in order to live a life devoted to religious ends—who may or may not practice the techniques commonly understood to constitute yoga. While not all these yogis practice yoga as such, it is among them that adept practitioners of yoga are most commonly found.

7. Geeti Sen, Paintings from the Akbar Nama (Calcutta: Rupa and Co., 1984), pp. 15–18. In the discussion after I presented some of the material in this paper at the European Conference on South Asian Studies in Lisbon, July 2012, it was suggested that Mughal depictions of yogis might be derived from archetypes and are thus unreliable historical witnesses. This is disproved by two features of the images themselves. First, with a handful of obvious exceptions when whole paintings are derivative of others, the yogis in the many Mughal pictures I have seen are all very different from one another. Second—to draw an analogy from philology—were the pictures to be derived from archetypes rather than firsthand observation, we would expect a situation similar to that found in the vast majority of Indic manuscript stemmata, in which “contamination,” caused by a scribe consulting more than one manuscript of a text when transcribing a new one, renders stemmatic analysis (the mechanical identification of archetypes) impossible. In Mughal painting, this would manifest in yogis from one tradition being depicted with the attributes of another; i.e., were an artist to work from older paintings rather than from real life, we would expect him to pick and choose traits indiscriminately (just as the name yogi is indiscriminately applied to ascetics of various sects in our written sources). Yet, despite there being several hundred very diverse Mughal depictions of yogis, there is none of the contamination that would result from such practices: the sect-specific features outlined in this article are never found out of place. We do not see Gorakhnāthi yogis with Saṃnyāsī features or vice versa: no yogis wearing Gorakhnāthi siṅgīs are depicted naked or with big dreadlocks; no Saṃnyāsīs wear the multicolored Gorakhnāthi necklace; no Gorakhnāthis perform physical austerities; and so forth.

8. Many aspects of the lives of yogis are rarely, if ever, recorded in writing, and these paintings are often our only historical sources about them. See for example Hope Marie Childers, “The Visual Culture of Opium in British India” (PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 2011), p. 18, on depictions of drug consumption by ascetics in premodern India.

9. This paragraph summarizes Mallinson, “Śāktism and Haṭhayoga.”

10. On these late medieval texts and their wholesale incorporation of verses—sometimes even entire texts—from the early haṭhayoga corpus, see Christian Bouy, Les Nātha-Yogin et Les Upaniṣads (Paris: De Boccard, 1994).

11. References to women practitioners of haṭhayoga are very rare in the texts at our disposal; where stated, the female equivalent of semen is said to be menstrual fluid (e.g., Haṭhapradīpikā of Svātmārāma, ed. Svāmī Digambarjī and Dr Pītambar Jhā [Lonavla: Kaivalyadhām S. M. Y. M. Samiti, 1970], 3.95).

12. James Mallinson, “Siddhi and Mahāsiddhi in Early Haṭhayoga,” in Yoga Powers, ed. K. A. Jacobsen (Leiden: Brill: 2012), pp. 327–44.

13. Dattātreyayogaśāstra, 41a–42b:

brāhmaṇaḥ śramaṇo vāpi bauddho vāpy ārhato ’thavā|

kāpāliko vā cārvākaḥ śraddhayā sahitaḥ sudhīḥ||

yogābhyāsarato nityaṃ sarvasiddhim avāpnuyāt|

From an unpublished critical edition by James Mallinson, based on the following witnesses: Dattātreyayogaśāstra, edited by Brahmamitra Avasthī, Svāmī Keśavānanda Yoga Saṃsthāna (1982); Man Singh Pustak Prakash nos. 1936; Wai Prajñā Pāṭhaśālā 6/4–399, 6163; Baroda Oriental Institute 4107; Mysore Government Oriental Manuscripts Library 4369; Thanjavur Palace Library B6390. The edition was read by Alexis Sanderson, Jason Birch, Péter-Dániel Szántó, and Andrea Acri at Oxford in early 2012, all of whom I thank for their valuable emendations and suggestions.

14. The earliest references to the wearing of earrings by ascetics are in the context of Mahayana Bodhisattvas and tantric Siddhas (see n. 53 for references).

15. The ascetic practice of sitting under the sun surrounded by fires is attested in textual and visual sources from before the Common Era, but the archetypal ascetic practice of living around a smoldering dhūni fire, found to this day, is not represented in images prior to the Mughal period. Orthodox brahmin ascetics are enjoined to renounce the use of fire, but it seems fair to assume that heterodox ascetics living away from society have always used fire to cook and keep warm and that the practice itself is not an innovation of the Mughal era, only its depiction.

16. The consumption of cannabis arrived in India with Islam. Cannabis first appears in Ayurvedic texts in the eleventh century (G. J. Meulenbeld, “The search for clues to the chronology of Sanskrit medical texts as illustrated by the history of bhaṅgā,” in Studien zur Indologie und Iranistik 15 [1989], p. 64; D. Wujastyk, “Cannabis in Traditional Indian Herbal Medicine,” in Āyurveda at the Crossroads of Care and Cure, Proceedings of the Indo-European Seminar on Ayurveda, Arrábida, Portugal, November 2001, ed. A. Salema [Lisboa & Pune: Centro de História del Além-Mar, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2002], pp. 45–73) and was probably introduced into the ascetic milieu by Madariyya fakirs in the fourteenth to fifteenth century (Alexis Sanderson, “The Śaiva religion among the Khmers: part I,” Bulletin del École Française D’extréme-Orient 90–91 [2003], p. 265, n. 43). Prior to the arrival of tobacco in India at the beginning of the seventeenth century, cannabis was eaten or drunk, not smoked, and I know of no pictures of ascetics smoking cannabis that date to earlier than the eighteenth century.

17. It seems likely that at some point, perhaps in the seventeenth century, certain Nāth lineages were absorbed into the Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsī order (see n. 46 ).

18. Gorakṣa or Gorakṣanātha is his Sanskrit name; in Hindi and other vernacular languages he is known as Gorakh or Gorakhnāth.

19. The combination of the two traditions’ yogas was universally accepted, but to this day each displays a predilection for the methods it originated. Thus āsana practice is found among the Rāmānandīs and Daśanāmīs but is almost absent among the Nāths, while the latter are renowned for their mastery of Tantric ritual and yoga (Mallinson, “Śāktism and Haṭhayoga”).

20. The first references to the Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsīs and Nāths as formalized orders are found in Sikh works from approximately 1600: (Śrī) Guru Granth Sāhib, with complete index prepared by Winand M. Callewaert, 2 parts (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1996), p. 939, 7.3, 9.2; p. 941, 34.2; Vārāṅ Bhāī Gurdās, ed. Jodh Singh (Patiala: Vision & Venture, 1998), 8.13. It seems that the formalization of the Rāmānandīs did not happen until the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century, when their akhāṛās were first organized in Rajasthan (see Monika Horstmann, “Power and Status: Rāmānandī Warrior Ascetics in 18th-Century Jaipur” in Asceticism and Power in South and South East Asia, ed. P. Flügel and G. Houtman [London: Routledge, forthcoming]).

21. There are three accounts of this encounter, in which the combatants are referred to inconsistently as both Jogīs and Saṃnyāsīs. Ahmad and Al-Badauni say that they are Jogīs and Saṃnyāsīs (Nizamuddin Ahmad, “Tabakat-i Akbari,” in The History of India as Told by Its Own Historians, trans. H. M. Elliot and J. Dowson, vol. 5 [London: Trubner and co., 1873], p. 318; Al-Badauni, Muntakhabu-t-Tawārīkh, vol. 2, trans. W. H. Lowe [Calcutta: Asiatic Society, 1898], p. 95). Abu’l Fazl says that both sides are Saṃnyāsīs, identifying one group as Kurs, the other as Purīs (H. Beveridge, The Akbar-nāma, trans. from Persian, vol. 2. Bibliotheca Indica: A Collection of Oriental Works published by the Asiatic Society of Bengal [Delhi: Rare Books, 1972], p. 423). Kur is a corruption, resulting from Persian orthography, of Giri. This is supported by the list of the Daśanāmīs’ ten names given in the Dabistān, where in the place of Giri we find Kar (David Shea and Anthony Troyer, The Dabistān: or School of Manners [London: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland, 1843], p. 139; cf. ibid., pp. 147–48, which mentions a Saṃnyāsī called Madan Kir).

22. H. Beveridge, The Akbar-nāma, vol. 3, pp. 514, 528.

23. As noted by Ellen Smart, “Paintings from the Bāburnāma: A Study of Sixteenth-Century Mughal Historical Manuscript Illustration” (PhD diss., School of Oriental Studies, University of London, 1977), pp. 221–40, the illustration of Bābur’s visit to Gurkhattri in fig. 3 is likely to be derivative of a single folio from the text now found in the Victoria and Albert Museum (IM 262-1913). There are no significant differences in the two paintings’ depictions of the yogis’ features under consideration in this essay.

24. George Weston Briggs, Gorakhnāth and the Kānphaṭa Yogīs (1938; repr. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1998), p. 98.

25. In 2011 the Gorakhnāth temple at Gurkhattri was reopened to Hindus after sixty years (Hindustan Times, November 1, 2011).

26. Annette Susannah Beveridge, The Babur-nama in English (London: Luzac and Co., 1922), p. 230.

27. It would perhaps be more accurate to call them “proto-Nāths”: the name Nāth was yet to be applied to an order of human ascetics (James Mallinson, “Nāth Saṃpradāya,” Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism, vol. 3, ed. Knut A. Jacobsen [Leiden: Brill, 2011], p. 409).

28. I note here some rare exceptions to this principle. The Nāth followers of Mastnāth eschew wearing the siṅgī, claiming to have internalized it (Rājeś Dīkṣit, Śrī Navnāth Caritr Sāgar [Delhi: Dehati Pustak Bhaṇḍār, 1969], p. 22; Hazārīprasād Dvivedī, Nāth Sampradāy [Ilāhābād: Lokbhāratī Prakāśan, 1996], p. 17). The icon of Bābā Bālaknāth and the Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsī priests at his temple at Dyot Siddh in Himachal Pradesh wear very small siṅgīs, even though, according to legend, Bābā Bālaknāth was avowedly not a Nāth; he defeated Gorakhnāth in a magical contest. On March 24, 2009, I asked the current mahant, Rājendra Giri—who sports a fine golden siṅgī and is, as his name suggests, a member of the Giri suborder of the Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsīs—why he wore what I thought was a Nāth emblem. He told me that the siṅgī itself has no particular sectarian connotation. It may be that Bābā Bālaknāth’s lineage constituted one of the maḍhi divisions of the Giri suborder of the Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsīs. All twenty-seven of the Giri maḍhis have names ending in -nāth and are said to trace their lineage back to one Brahm Giri, who defeated Gorakhnāth in a display of siddhis, after which he took the name Augharnāth (Śrī Mahant Lāl Purī, Daśanām Nāgā Saṃnyāsī evaṃ Śrī Pancāyatī Akhāṛā Mahānirvāṇī [Prayāg: Śrī Pancāyatī Akhāṛā Mahānirvāṇī, 2001], pp. 66–69). Bābā Bālaknāth is sometimes identified with Jālandharnāth, and this myth may represent the still unsettled rivalry between the more Tantric Jālandharnāth and the reformist/heretical Gorakhnāth: there are followers of the former who refuse to accept the latter as the founding guru and tutelary deity of the Nāth order (personal communication, Kulavadhuta Satpurananda, July 16, 2010; see also http://tribes.tribe.net/practicaltantra/thread/1e75639b-474a-4ed6-872e-0675b3b286c0). The Siddhānt Paṭal, a ritual handbook used by the Rāmānandīs and attributed to Rāmānand, mentions siṅgīs three times (pp. 2 l.2, 9 l.2, and 17 l.1). Bālyogī Śrī Rām Bālak Dās, a Rāmānandī Tyāgī, informed me on October 27, 2012, that in this context siṅgī refers to tiger’s claws when worn in pairs as an ornament on a Rāmānandī’s jaṭā or dreadlocks. The Ṣoḍaśamudrā, of which I have seen a single circa seventeenth- or eighteenth-century manuscript (Thanjavur Saraswati Mahal Library, B6385), includes the siṅgī among the accoutrements of a yogi but makes no mention of anything specifically Nāth. The text is ascribed to Śuka Yogī. Śuka, son of Vyāsa, is said to practice yoga in the Mahābhārata (12.319), and the Bhāgavatapurāṇa is framed as a discourse by Śuka to King Parīkṣit. Śuka is not included in Nāth lineages but is mentioned frequently in those of the Rāmānandīs (e.g., Monika Horstmann, “The Rāmānandīs of Galta (Jaipur, Rajasthan),” in Multiple Histories: Culture and Society in the Study of Rajasthan, ed. Lawrence A. Babb, Varsha Joshi, and Michael W. Meister [Jaipur: Rawat Publications, 2002], p. 173) and is among the traditional teachers (ācāryas) of the Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsīs (Matthew Clark, The Daśanāmī-Saṃnyāsīs: The Integration of Ascetic Lineages into an Order [Leiden: Brill, 2006], p. 116, n. 46; Purī, Daśanām Nāgā Saṃnyāsī, p. 21).

29. See Miragāvatī of Kutubana: Avadhī text with critical notes, ed. D. F. Plukker (Thesis Universiteit van Amsterdam, 1981), 106g; Padmāvatī of Jayasī = The Padumāwati of Malik Muḥammad Jaisi, ed. G. A. Grierson and S. Dvivedi (Calcutta: Asiatic Society, 1911), 12.1.4; , Madhumālatī 173 (Aditya Behl and Simon Weightman with Shyam Manohar Pandey, Madhumālatī: An Indian Sufi Romance [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000], p. 72); Dādū sākhī 25.20, pads 213.2, 214.2; Kabīr granthāvalī pads 142.3, 172.1; Nāmdev pads 52.1, 64.2; Hardās pads 1.3, 25.0; Gorakh pad 19.3, 60.4; Sundardās pads 122.2, 144.2; Gurugranth 145.1, 208.5, 334.18, 360.2, 605.12, 730.11, 730.17, 877.9, 886.14, 907.15, 908.13, 970.16. Pañc Mātrā 11, 15, 19. (Winand M. Callewaert and Bart Op De Beeck, Devotional Hindī Literature: A Critical Edition of the Pañc-Vāṇī or Five Works of Dādū, Kabīr, Nāmdev, Rāidās, Hardās with the Hindī Songs of Gorakhnāth and Sundardās, and a Complete Word-index, 2 vols. [New Delhi: Manohar, 1991]).

30. Bhāvanāpuruṣottamam of Ratnakheta Śrīnivāsa Dīkṣita, ed. S. Swaminātha Sastri, Tanjore Sarasvati Mahal Series, no. 167 (1979), p. 98. I am grateful to Péter-Dániel Szántó for pointing out this reference to me.

31. Sekaśubhodaya of Halayudha Miśra, ed. and trans. Sukumar Sen, Bibliotheca Indica Series 286 (Kolkata: Asiatic Society, 1963), introduction, pp. x–xi. This text is a fictitious account of a Muslim shaykh (seka) overcoming yogis and brahmins.

32. Harimohan Mishra, the editor of the early fifteenth-century Maithili Gorakṣavijaya, suggests that siṅgīs may be referred to in that text’s third gīt although the reading is unclear (p. 28). The circa 1700 Siddhasiddhāntapaddhati, a Nāth sectarian text, includes siṃhanāda among the accoutrements of the yogi (5.15). Gorakṣavijaya of Vidyāpati, ed. Harimohan Miśra (Paṭnā: Bihār Rāṣtrabhāṣā Pariṣad, 1984). Siddhasiddhāntapaddhati of Gorakṣanātha, ed. M. L. Gharote and G. K. Pai (Lonavla: Lonavla Yoga Institute, 2005).

33. The earliest references to Gorakṣa are from South India, in particular the Deccan (Mallinson, “Nāth Saṃpradāya,” p. 411).

34. Mahdi Husain, The Reḥla of Ibn Battūta (Baroda: Oriental Institute, 1953), p. 166; George Percy Badger, The Travels of Ludovico di Varthema in Egypt, Syria, Arabia Deserta and Arabia Felix, in Persia, India and Ethiopia, A.D. 1503 to 1508. Translated from the original Italian Edition of 1510, with a Preface, by John Winter Jones, Esq., F.S.A., and edited, with notes and an introduction, by George Percy Badger (London: The Hakluyt Society, 1863), p. 112; Vasundhara Filliozat, Vijayanagar as seen by Domingo Paes and Fernao Nuniz (16th Century Portuguese Chroniclers) and others (Delhi: National Book Trust, 1999), p. 79; Mansel Longworth Dames, The Book of Duarte Barbosa. An account of the countries bordering on the Indian Ocean and their inhabitants, written by Duarte Barbosa, and completed about the year 1518 a.d., vol. 1 (London: Hakluyt Society, 1918), p. 231.

35. Elinor Gadon, “Note on the Frontispiece,” in The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India, ed. Karine Schomer and W. H. McLeod (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1987), p. 420.

36. Victoria and Albert Museum, I.S. 94-1965.

37. See William R. Pinch, “Nāth Yogīs, Akbar, and Bālnāth Ṭillā,” in Yoga in Practice, ed. David Gordon White (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), pp. 273–88 for historical accounts of Bālnāth Ṭillā. The Ṭillā came to be known as Gorakh Ṭillā in the process of the various disparate Nāth lineages uniting under Gorakh (see Mallinson, “Nāth Saṃpradāya”). The earliest reference to it by this name that I have found is in the Saṃnyāsī Pūrṇ Purī’s translated account of his travels in the second half of the eighteenth century, in which it is referred to as “Gorakh-tala”). Pūrṇ Purī, “His account of his travels, published as ‘Oriental Observations, No. X—The Travels of Prán Puri, a Hindoo, who travelled over India, Persia, and Part of Russia,’” in The European Magazine and London Review 57 (1792, published in 1810), p. 269.

38. J. S. Hoyland, The Commentary of Father Monserrate, S. J., On His Journey to the Court of Akbar (London: Oxford University Press, 1922), p. 114.

39. Monserrate himself wrote: “Dignitatis insigne, est, infula bombycinis fasciolis, è fastigio, per gyrum infulae, ordine affixis, quae impendeant, et facile moueantur · tribus, quattuorue || ordinibus, a fastigio, ad extremam infulae oram, quae frontem cingit” (Mongolicae Legationis Commentarius, p. 597). Hoyland (see n. 38) omits from his translation the last part of Monserrate’s description of the bands of silk: “ordinibus, a fastigio, ad extremam infulae oram, quae frontem cingit” (in rows, from the top to the edge of the fillet, they encircle the forehead). Curiously, although fillets matching Monserrate’s description are not found in contemporaneous images of Nāths, they are found in two more recent paintings. A late eighteenth-century painting of a “Kun Futta or Ear Bor'd Joguee” in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art (B1977.14.22254) depicts a Nāth ascetic wearing a conical hat from which hang strips of cloth (I thank Holly Shaffer for bringing this picture to my attention), and a similar headpiece is sported by Jālandharnāth in figure 12.

40. My enquiries among Nāths today about these insignia have drawn a blank, and despite their prominence in Mughal paintings I have not seen them in eighteenth-century or later depictions of Nāths.

41. Monserrate’s statement that these necklaces are the mark of senior Nāths is not borne out by Mughal paintings, in which young Nāths serving older yogis can be seen wearing them. I thank Debra Diamond for this observation.

42. Amongst the earliest examples (pre-1605) are the following: Prince and Princess Sadruddin Aga Khan collection M.286 (Sheila R. Canby, Princes, Poets, and Paladins: Islamic and Indian Paintings from the Collection of Prince and Princess Sadruddin Aga Khan [London: British Museum Press, 1998], p. 109; Rajesh Bedi and Ramesh Bedi, Sadhus: The Holy Men of India [Delhi: Brijbasi, 1991], p. 94 (this picture is said to be in the Jaipur Savai Man Singh II Museum, but staff there are currently unable to locate it—I thank Giles Tillotson for this information); British Library J.22,16; Gulshan Album, fol. 13b, no. 1, Stadstbibliothek; Chester Beatty Library Baḥr al-Ḥayāt manuscript (see cats. 9a–j, Yoga: The Art of Transformation); Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, 1988.27; Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University, 2002.50.29; Chester Beatty Library, In 44.3; Chester Beatty Library, Yogavāsiṣṭha, In 05, f.304a; Chester Beatty Library, Mrigāvatī, In 37 f.25a, f.28b, f.44a; Walters W.596 f.22b (dated 1593, another illustration of the Bāburnāma description of Bābur’s visit to Gurkhattri); Bāburnama, Cynthia Hazen Polsky Collection, New York (see cat. 15a, Yoga: The Art of Transformation); Bāburnama, Victoria and Albert Museum, IM 262-1913; Bāburnama, British Library, Or. 3714, f. 197r.

43. Saṃnyāsīs generally have bigger and longer jaṭā than Nāths, a distinction still found. Today’s Saṃnyāsīs and Rāmānandīs only shave their heads at initiation and the death of a guru, while many Nāths keep their hair short or shaven. An exception to the principle of Saṃnyāsīs being best identified by the absence of Nāth features is their consumption of cannabis. At the bottom left of fig. 1, members of the Saṃnyāsī camp are shown straining a paste of cannabis in preparation for drinking it. In contrast with their later reputation as heavy consumers of intoxicants, no Mughal depictions of Nāths show them using cannabis.

Although Nāths in Mughal depictions are never naked, later traditions do speak of naked Nāths. Thus tapasvī Nāths such as Raṇpatnāth and Māndhātānāth of Asthal Bohar and Amṛtnāth of Shekhavati are usually portrayed naked in hagiography and statuary (V. Bouillier, Itinérance et vie monastique: Les ascètes Nāth Yogīs en Inde contemporaine [Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 2008] plate 43 and p.267).

44. Early Mughal pictures of Saṃnyāsīs include the following (here I include pre-1650 pictures): San Diego Museum of Art, 1990:355; British Museum, 1941,0712,0.5; British Museum, 1920,0917,0.38; pl. 231 in The St. Petersburg Muraqqa‘; Two Ascetics, Museum Rietberg Zürich; “Yogi with Servants,” reproduced on p. 118 of “Caricature and Satire in Indian Miniature Painting: From the Collection of Ludwig V. Habighorst” in Indian Satire in the Period of First Modernity, ed. Monika Horstmann and Heidi Pauwels (Wiesbaden: Harassowitz, 2012), pp. 117–32.

45. On the Nāths’ lack of observance of purity rules in the Mughal era, see Shea and Troyer, The Dabistān, p. 129; and Dames, The Book of Duarte Barbosa, p. 232.

46. Because of the perennial confusion caused by the ambiguity of the name yogi, various scholars have alleged that the Nāths were India’s first organized military order (see, e.g., David Lorenzen, “Warrior Ascetics in Indian History,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 98 [1978], p. 68; cf. Véronique Bouillier, “La Violence des Non-violents ou les Ascètes au Combat,” Puruṣārtha 16 (1993), p. 218, who is surely correct when she writes of non-Muslim ascetics, “Ce sont donc les Dasnāmī Sannyāsīs … qui sont les premiers à ainsi instaurer dans leurs rangs une branche combatante.” With some early localized exceptions, such as the warrior yogis in the service of the King of the Yogis on India’s west coast in the early sixteenth century (Badger, The Travels of Ludovico di Varthema, pp. 273–74) and the armies of yogis mentioned in two Sufi romances, the Padmāvati (Jogī khaṇḍ) and Kanhāvat of Malik Muhammad Jāyasī, ed. Parameśvarī Lāl Gupta (Vārāṇasī: Annapūrṇā Prakāśana, 1981), p. 342, there are no indications that Nāths were ever organized into fighting forces: they are not mentioned in the many accounts of battles between groups of ascetics from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century (see, e.g., Clark, The Daśanāmī-Saṃnyāsīs, pp. 61–64), or ever portrayed bearing weapons in our pictorial sources. Two or three Nāths are seen on the edges of the battle depicted in figures 2 and 3, but they are not involved in the action. There has long been friendly interaction between the Saṃnyāsīs and Nāths, and at some point it appears that certain Nāth lineages were absorbed into the Dasnāmīs, in particular into their Giri suborder (see n. 17 ). It may be that Saṃnyāsī military units were joined by some early isolated groups of militarized proto-Nāths, such as those encountered by Tavernier in 1640 (V. Ball, trans., Travels in India by Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, Baron of Aubonne. Translated from the original French edition of 1676 with a biographical sketch of the Author, Notes, Appendices &c., 2 vols. [Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1995], pp. 66–68), who were perhaps members of the army of the Malabar King of the Yogis exiled after the oppression of his monastery at Kadri by Veṅkāṭappa Nāyaka. A single warrior in the thick of the Akbarnāma depiction of the Thaneshwar battle can be seen wearing a siṅgī on a thread wrapped around his turban. Today, after being initiated, Nāths vow not to “keep dangerous weapons” (H. A. Rose, A Glossary of the Tribes and Castes of the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province, vol. 2 [Lahore: Superintendent, Government Printing, Punjab, 1911], p. 401) and the first Sanskrit Nāth text written after the formalization of the order, the Siddhasiddhāntapaddhati of Gorakṣanātha, ed. M. L. Gharote and G. K. Pai (Lonavla: Lonavla Yoga Institute, 2005), 6.94, scorns those who carry arms.

47. See Carl W. Ernst, “The Islamization of Yoga in the Amrtakunda Translations,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, s. 3, vol. 13, no. 2 (2003), pp. 1–23; and Kazuyo Sakaki, “Yogico-tantric Traditions in the Ḥawd al-Ḥayāt,” Journal of the Japanese Association for South Asian Studies 7 (2005), pp. 135–56.

48. See Bouillier, “La Violence des Non-violents ou les Ascètes au Combat,” pp. 22–23, on the wearing of earrings by ascetic Nāths; and Daniel Gold, “Experiences of Ear-Cutting: the Significances of a Ritual of Bodily Alteration for Householder Yogis,” Journal of Ritual Studies 10, no. 1 (1996), pp. 91–112; Gold, “Nāth Yogis as Established Alternatives: Householders and Ascetics Today,” Journal of Asian and African Studies 34, no. 1 (1999), pp. 68–88; Gold, “Yogis’ Earrings, Householder’s Birth: Split Ears and Religious Identity among Householder Nāths in Rajasthan,” in Religion, Ritual and Royalty, ed. N. K. Singhi and Rajendra Joshi (Jaipur and New Delhi: Rawat Publications, 1999), pp. 35–53, on Rajasthani householder Nāths. See also Briggs, Gorakhnāth and the Kānphaṭa Yogīs, pp. 6–11; Hazārīprasād Dvivedī, Nāth Sampradāy (Ilāhābād: Lokbhāratī Prakāśan, 1996), pp. 15–16.

49. A few Rāmānandī Nāgās wear pendant earrings of tulsī wood and some Udāsin ascetics wear small, silver, stud earrings in the shape of a crescent moon. As far as I am aware, however, no Saṃnyāsīs wear earrings. Briggs, Gorakhnāth and the Kānphaṭa Yogīs, pp. 6–7, reports that members of the Gūḍara subsect of the Saṃnyāsīs wear kānphaṭā-style earrings and that their founder, Brahm Giri, is said to have been initiated into the practice of wearing earrings by Gorakhnāth; cf. Purī, Daśanām Nāgā Saṃnyāsī,pp. 66–69; and Surajit Sinha and Baidyanāth Saraswati, Ascetics of Kashi: An Anthropological Exploration (Varanasi: N. K. Bose Memorial Foundation, 1978), pp. 93–94. A picture of a Gūḍara ascetic wearing hooped earrings through his earlobes can be seen on page 35 of the Riyāz al-madhāhib (British Library, APAC Add.24035), which was written and illustrated in 1812.

50. From the time of the second-century BCE Gudimalla liṅga (see, e.g., M. C. Choubey, Lakulīśa in Indian Art and Culture [Delhi: Sharada Publishing House, 1997], pl. 2), Indian deities have regularly been depicted as wearing earrings, which are usually hooped.

51. Mahābhārata 3.300–310 tells the story of the robbing of Karṇa’s magical earrings. Rāmāyaṇa 2.14.2 mentions young men wearing polished earrings. Manu includes earrings among the obligatory apparel of a follower of Viṣṇu (Manusmṛti: with the Sanskrit Commentary Manvartha-Muktavali of Kulluka Bhatta, ed. J. L. Shastri [Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1983], 4.3). Descriptions of the karṇavedha rite in which boys’ or girls’ ears are pierced are found in the following dharmaśāstra texts (I am grateful to Shingo Einoo for providing me with these references: Kauṣītaka Gṛhyasūtra 1.20.1-8 (The Kauṣītaka Gṛhyasūtras, with the Commentary of Bhavatrāta, ed. T. R. Chintamani [New Delhi: Panini, 1982]); Bodhāyanagṛhyaśeṣasūtra 1.12 (Bodhāyana Gṛhyasūtram of Bodhāyana Maharṣi, ed. L. Srinivasachar and R. Sharma Sastri, Oriental Research Institute Series No. 141 [Mysore: University of Mysore, Oriental Research Institute, 1983], pp. 1–127); Suśrutasaṃhitā sūtrasthāna 16.1-48 (Suśrutasaṃhitā ḍalhaṇācāryakṛtanibandhasaṃgrahākhyaṭīkayā, Nṛpendranāthasenaguptena Balāicandrasenaguptena ca saṃpāditā saṃśodhitā prakāśitā ca, part 1 [Calcutta: C. K. Sen and Company Limited, 1937/38]); Viṣṇudharmottarapurāṇa 2.52.75cd-83 (The Viṣṇudharmottarapurāṇam (Delhi: Nag Pubishers, 1985); Vīramitrodaya 258, 5-263, 15 (Vīramitrodaya. paribhāṣā, prakāśa by Mitra Miśra, ed. Pārvatīya Nityānanda Śarmā, Chokhamba Sanskrit Series, nos. 103 & 108 [Benares: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Book-depot, 1906. Strabo, drawing on Megasthenes, says that Indian philosophers, after thirty-seven years of asceticism, live “with less restraint” and wear “robes of fine linen, and rings of gold, but without profuseness, upon the hands and in the ears” (W. Falconer, trans., The Geography of Strabo, vol. 3 [London: Henry G. Bohn, 1857], p. 109). In Bāṇa’s Harṣacarita, which dates to the first half of the seventh century, kings are said to wear both “dangling pendants” and “ear-pendants in the form of leaves or scroll-work” (V. S. Agrawala, The Deeds of Harsha: Being a cultural study of Bāṇa’s Harshacharita [Varanasi: Prithivi Prakashan, 1969], p. 187; both types of earring are illustrated on p. 188, figs. 83–85). In an early thirteenth-century account, Chag lo Chos rje dpal the younger, a Tibetan monk, reports that, “A sign of low caste was the absence of perforation (hole) in the ears. Others had holes in their ears.” (G. Roerich, The Biography of Dharmasvamin [Patna: K. P. Jayaswal Research Institute, 1959], p. 85; I am grateful to Péter-Dániel Szántó for pointing out this reference to me).

52. Daud Ali, “Technologies of the Self: Courtly Artifice and Monastic Discipline in Early India,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 41, no. 2 (1998), p. 176, notes how the Cullavagga, a Pali vinaya text, prohibits monks from wearing earrings.

53. See, for example, the many depictions of bodhisattvas in Marilyn M. Rhie and Robert Thurman, Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1991) and of siddhas in Rob Linrothe, ed. Holy Madness: Portraits of Tantric Siddhas (New York and Chicago: Rubin Museum of Art and Serindia Publications, 2006). Several of the siddhas depicted in thirteenth- to fourteenth-century carvings at the Panhale-Kaji caves in the Konkan wear hooped earrings in their earlobes (M. N. Deshpande, The Caves of Panhāle-Kāji (Ancient Pranālaka) [New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, 1986], pls. 29, 30, 58ABC, 59, 60, 61, 62). The carvings made in 1510–11 on the wall enclosing the temple complex at Shrishailam also depict various siddhas wearing earrings (see Richard Shaw, “Srisailam: Centre of the Siddhas,” South Asian Studies 13 [London: Oxford and IBH Publishing, 1997], figs. 10, 13).

54. Yāmuna’s Āgamaprāmāṇyam includes earrings among the six insignia of a Kāpālika (verse 83; cf. David Lorenzen, “A Parody of the Kāpālikas,” in Tantra in Practice, ed. David Gordon White [Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000], p. 83, where an inscription from 1050 is cited in which a Mahāvratin, another name for a Kāpālika, is said to bear the six insignia). A Kāpālika yogi described in a verse ascribed to Kṛṣṇācāryapāda (Siddha Caryāgīti 11), which can be dated to somewhere between the eighth and twelfth centuries, is said to wear earrings; cf. Siddha Caryāgīti 28.3; see Per Kvaerne, An Anthology of Buddhist Tantric Songs (Bangkok: Orchid Press, 1986). Earrings are said to be the distinguishing mark of Kāpālika practitioners in Nirmalamaṇi’s commentary on the Aghoraśivācāryapaddhati, Aghoraśivācāryaviracitā Kriyākramadyotikākhyā Paddhatiḥ, Nirmalamaṇiguru-viracitā Prabhākhyā Kriyākramadyotikāvyākhyā (Cidambaram, 1927), p. 447. In the Maitrāyaṇīyopaniṣad, ed. J. A. B. van Buitenen (The Hague: Mouton and Co., 1962), 7.8, Kāpālikas are said to wear red earrings (Alexis Sanderson, “The Śaiva Age,” in Genesis and Development of Tantrism, ed. Shingo Einoo [Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009], p. 179, n. 435; in the same note Sanderson cites examples from the Jayadrathayāmala and Picumata of earrings being among the six insignia of the Kāpālikas). The pupil of the Kāpālika follower of Gorakṣanātha in the early sixteenth-century Bhāvanāpuruṣottama is called Māyākuṇḍalin, “he who wears the earrings of Māyā.” He describes the fearsome dress of another Tantric practitioner, which includes earrings (pp. 98–101). In a long list of religious practices, Sundardās, a seventeenth-century follower of Dādū, mentions the wearing of earrings by Kāpālikas (Sarvāṅgayogapradīpikā 1.18).

55. See, e.g., Miragāvatī 106c; Padmāvatī 12.1.6; Dādū pads 213.2, 214.2; Gorakh pads 19.3; Kabīr Granthāvalī pad 172.1, 175.2; Hardās pads 61.1; Sundardās sākhī 16.23, pads 135.1, 144.1; Gurugranth 6.16, 155.16, 208.2, 334.16, 359.18, 526.2, 730.11, 835.6, 856.19, 879.18, 908.11, 939.4, 939.6, 940.5, 940.11, 952.2, 970.14; Madhumālatī 172 (Behl and Weightman, p. 72).

56. The manuscript was completed in 1825. The same two yogis are accompanied by four more ascetics in a painting by Ghulam Ali Khan or an artist of his circle from circa 1820–25. All six ascetics are named in accompanying inscriptions. The larger painting is reproduced in Archeologie, Arts d’Orient, July 2, 1993, p. 61, no. 185; and Joachim K. Bautze, Interaction of Cultures: Indian and Western Painting 1780–1910. The Ehrenfeld Collection (Alexandria, VA: Art Services International, 1998), pp. 56–57. In the former, the ascetic on the left in the Tashrīḥ al-aḳvām picture is said to be called “Awglohl (?) Jogi”; in the latter, “Awgahal Jogi.” The ascetic on the right is likewise said to be called “Shandbu Nanha (Nâth ?) Jogi” and “Shanbu Nanha [?] Jogi.” The ascetic on the right is depicted on his own in a picture from a private collection reproduced in Christopher Bayly, ed. The Raj: India and the British 1600–1947 (London: National Portrait Gallery Publications, 1990), p. 223, pl. 283, in which his earrings are in the lobes of his ears, not kānphaṭā-style. On p. 323 of the Tashrīḥ al-aḳvām is a picture of a Sanpera or snake-charmer with earrings in the cartilages of his ears. Several snake-charmer castes claim affiliation with the Nāth tradition, which became an umbrella organization for a broad variety of religious specialists with roots in the tantric traditions. Snake-charmers have an old Tantric pedigree, as evinced by the Gāruḍa Tantras, on which see Michael J. Slouber, “Gāruḍa Medicine: A History of Snakebite and Religious Healing in South Asia” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2012). A slightly earlier picture (1815–20), also in the British Library collection (Add.Or.114), shows a “Kaun Fauttah (Beggar)” in Varanasi with earrings in the cartilages of his ears. The change in the position of the Nāths’ earrings is highlighted by a comparison between a circa 1605 painting of a Nāth group (Rajesh Bedi and Ramesh Bedi, Sadhus: The Holy Men of India [Delhi: Brijbasi, 1991], p. 94) and a nineteenth-century depiction of Nāths from Lucknow (The Scholar’s Vision: The Pal Family Collection, [New York: Christies, 2008], pl. 252, pp. 38–39) at whose center is found a reworking of the earlier image. In the older painting the yogis’ earrings are worn in their earlobes and in the later one they are worn kānphaṭā-style. Pramod Chandra, “Hindu Ascetics in Mughal Painting,” in Discourses on Śiva: Proceedings of a Symposium on the Nature of Religious Imagery (Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 1985), p. 312, also noticed the absence of kānphaṭā-style earrings in early Mughal pictures: “Actually, and rather surprisingly, I have yet to see an early Mughal representation of the split ear and I wonder what to make of it. Could it be possible that the practice is more modern than is commonly thought?”

57. In 1505 or 1506, Ludovico di Varthema met “the king of the Ioghe” somewhere on India’s west coast and reported that he wore jewels in his ears (Badger, The Travels of Ludovico di Varthema, p. 112). One hundred and twenty years later, Della Valle visited the then incumbent “king of the Gioghi” at Cadiri. He was much impoverished compared to his predecessor because of the predations of King Venkaṭappa Nāyaka, but still wore golden earrings: “in either ear hung two balls, which seemed to be of Gold, I know not whether empty, or full, about the bigness of a Musket bullet; the holes in his ears were large, and the lobes much stretched by the weight” (Edward Grey, The Travels of Pietro Della Valle in India: From the Old English Translation of 1664 by G. Havers, 2 vols. [London: The Hakluyt Society, 1892], pp. 350–51).

58. The Silsila-i jūgiyān reports that “whenever a jogi takes a disciple, he cuts open the side of the disciple’s ear and inserts a ring of whalebone (Hindi kachkara) or crystal or something else of this type” (Carl W. Ernst, “Accounts of yogis in Arabic and Persian historical and travel texts,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 33 [2007], p. 421). The earliest usage of the name kānphaṭā that I have found dates to the same period (Travels of Prán Puri, p. 269, in which I take “Coonb’hatti” to be a transcription of kānphaṭā). Cf. the late eighteenth-century painting of a “Kun Futta or Ear Bor’d Joguee” in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art referred to in note 39; and F. V. Raper, “Narrative of a survey for the purpose of discovering the sources of the Ganges,” Asiatick Researches 11 (1810), p. 457: “The Jógis or Cánp’hatas are the disciples of Síva, as the Gosains; but, as the term Cánp’hata implies, they have a longitudinal slit in the cartilage of the ear, through which a ring, or plate, of horn, wood or silver, about the size of a crown piece, is suspended.”

59. Monika Horstmann, draft article “Emblems of Nāthyogīs,” May 2013.

60. The use of forms of the verb phaṭ/phaṛ/phāṛ in the context of ears strongly suggests the splitting of the cartilage rather than the piercing of the lobes, for which the usual terms are vernacular derivatives of Sanskrit karṇavedha/karṇachedana. I thank Monika Horstmann for this observation (personal communication, May 9, 2013).

61. Ascetics other than Nāths continued to wear hooped earrings into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Ivan Stchoukine, Les Miniatures Indiennes de l'Époque des Grands Moghols au Musée du Louvre (Paris: Librairie Ernest Leroux, 1929), p. 78, describes an eighteenth-century picture from Kangra in the Louvre that depicts three Vaiṣṇava sādhus, all of whom are wearing round earrings. Two Vairāgīs in a picture from Tamil Nadu dated 1830–35 and described in n. 93 both wear earrings. A depiction of the Saṃnyāsī Anūp Giri from the early part of the nineteenth century shows him wearing earrings (Pinch, Warrior Ascetics, p. 24). Two pictures from the late eighteenth century in the British Library appear to show Saṃnyāsīs wearing earrings: APAC J.45,37 and APAC Add.Or.2763.

62. For a reappraisal of the history of the Nāths, see Mallinson, “Nāth Saṃpradāya.”

63. This is the “Great Council of the All-India Yogis of the Twelve Orders who Wear Ascetic Garb” (Akhil Bhāratavarṣīya Avadhūt Bheṣ Bārah Paṃth Yogī Mahāsabhā; see V. Bouillier, Itinérance et vie monastique: Les ascètes Nāth Yogīs en Inde contemporaine [Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 2008], pp. 25–32).

64. See, e.g., Debra Diamond, Catherine Glynn, Karni Singh Jasol, Garden and Cosmos: The Royal Paintings of Jodhpur (Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 2008), p. 292.

65. E.g., commissions such as the Marwari Nāth Purāṇ in which Gorakṣa is raised to the level of a deity above other Nāth gurus (Viśveśvarnāth Reu, Nāth-caritr kī kathā aur uske ādhār par bane citroṃ kā vivaraṇ [Jodhpur: Jodhpur Government Press, 1937], pp. 3–4).

66. It may be that under the patronage of Maharaja Man Singh, who sponsored the gathering and copying of Nāth manuscripts from elsewhere in North India, the regional Jodhpur Nāth tradition established links with the expanding Gorakhnāthī tradition, with which it subsequently sought affiliation.

67. Diamond et al., Garden and Cosmos, cat. 33.