|

The Bible and the codex initially took shape within a Roman Empire that stretched from Syria to Scotland. Greek and Latin were the literary languages, and by fourth century Christianity was the state religion. In the early Middle Ages individual nations began to emerge, with their own languages, cultures, and religious traditions—orthodox Christian, heretical, and pagan—all influencing the ways in which Bible and book were perceived and produced. Still, the concept of "empire" continued to haunt ambitious leaders who saw faith as a way to unite their diverse subjects.

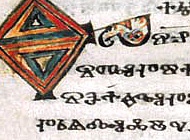

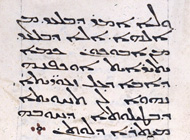

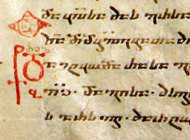

Disseminating a religion of the Word involved both finding interpreters to preach in local languages and teaching people sufficient literacy for reading and copying texts. Missionaries often used a written version of the spoken language while different sounds required the creation of suitable scripts. That was the case with ninth-century missionaries Saint Mesrob, who created the Armenian and the Georgian alphabets, and Saint Cyril, who developed what would become the Cyrillic alphabet.

For those who dedicated their lives to God's service, to be entrusted with the transmission of his Word was a high calling indeed. Books became channels of the Spirit, and gateways to revelation: for In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God (John 1:1).

From Babel to Pentecost

Christ's teachings first circulated orally in a local language called Aramaic, and throughout the Middle Ages, most people's knowledge of scripture continued to be oral and visual. They heard it through the public recitation of snippets of scripture and in sermons, poems, storytelling, and song. And they saw it in the images beautifying church buildings, carved on wayside crosses, or adorning the possessions of the wealthy. Psalters (books of psalms) and prayerbooks were used for public and private worship, while gospelbooks graced the shrines of saints and were used during services or displayed on the altar, where they also served to solemnify legal transactions and oaths.

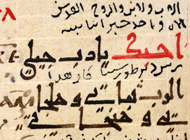

The transmission of scripture also promoted the use of written vernacular (local) languages. This development took on a different character in the East and West, shaped by varying cultural attitudes. Around the Mediterranean, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin were traditionally the "sacred languages" used for scripture. In western Europe, Latin—the common language of the Roman Empire—assumed this role. And while tension between "official" written languages and those spoken locally later became an issue in the West, there was no such tension in the Churches of the Christian Orient (Syriac, Coptic, Ethiopic, Armenian, Georgian). Indeed, the popularity of religious texts in local languages owed much to the desire of those regional Churches to preserve their own identities.

The book as desert, the scribe as evangelist

There were no rules governing how books of scripture were made in the Middle Ages. For some scribes it was part of the daily round of monastic life, conducted in collaboration with colleagues. Others preferred the more solitary model of early saints such as Paul and Anthony of Egypt, who sought spiritual challenge in the desert. Emulating those desert hermits, some scribes living in the watery wildernesses of northern Europe worked alone within the scribal desert of the book—a place of meditation, prayer, and encounter with the Divine.

The Italian monastic founder Cassiodorus (circa 485–580) lauded such scribal endeavor, writing that the scribe preaches with the pen and unleashes tongues with the fingers, and that each word written is a wound on Satan's body. In monasteries on the Atlantic seaboard, Saint Columba and other scribes were acclaimed as heroes.

Byzantine depictions of the evangelists helped to promote this concept by setting the scribe's labors against a timeless spiritual background of gold. Evangelist portraits also affirmed that the image of the book symbolized the scriptures of Christianity, just as the scroll did those of Judaism.

Women, too, served as scribal evangelists. Female scribes are known to have supplied books for churches and missions in England, France, and Germany.

From Eastern deserts to Western isles

During the early Middle Ages, monasteries in two far-flung regions—the desert sands of Egypt and the seascapes of Britain and Ireland—shared perceptions about the role of the book. The allure of the Holy Land, often visited by Westerners on pilgrimage, and a sense of their own remoteness from the Mediterranean world may have contributed to the fertile reception of eastern influence in Britain and Ireland.

Around 400 C.E., for example, a Coptic psalter was placed in the grave of an adolescent girl, reflecting the ancient practice of interring the Book of the Dead with the deceased. Likewise, in northeast England in 698 the relics of Saint Cuthbert were buried with a copy of Saint John's Gospel, bound using a complex Coptic sewing technique and a tooled leather cover. Book-shrines also were made in both regions, with their contents revered as relics themselves. The colorful griffins in the margins of the Lectionary of Mount Horeb have parallels in the lion symbols of Saint Mark in early Irish gospelbooks, such as the Macregol Gospels.

The traditions of East and West came together at the Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai. Founded between 548 and 565, it was home to Greek, Syrian, Arab, Georgian, Slavic, and Latin-speaking monks, who copied scriptural and liturgical books into their various languages.

The monastery also holds a few Latin manuscripts made before 1000, evidence that Latin speakers were in the region long before the Crusades. In 599, Pope Gregory the Great sent an envoy bearing gifts to Sinai, so there were evidently early communications between East and West.

Early Christian Britain and Ireland

As the Roman Empire contracted during the early fifth century, England was increasingly settled by pagan immigrants from Germany and southern Scandinavia—the Anglo-Saxons. Their conversion to Christianity gained impetus with a mission sent by Pope Gregory the Great and led by Saint Augustine, who arrived in Kent in 597.

The English, as the Anglo-Saxons became known, also had contact with missionaries from Ireland, which was introduced to Christianity in the fifth century. Irish monasteries produced books exuberantly written and decorated in Celtic fashion, such as the Macregol Gospels. Along with their English counterparts, they blended elements from Celtic, Germanic, Mediterranean, and Middle Eastern traditions to form a distinctive cultural style known as "Insular" (circa 550–850). English scribes produced striking copies of scripture such as the Cambridge-London Gospels, devised their own system of scripts and style of illumination, and followed the Irish example by introducing word-separation and systematic punctuation to clarify legibility.

The English and Irish also used their own languages to share the "good news" (in Old English, godspell). The scholar Bede, a monk in northeast England, admired the way Jews shared their scriptures with gentiles and encouraged the use of the English language to bring Christianity to others: on his deathbed in 735 he was translating Saint John's Gospel.

In the mid-tenth century, people started to translate gospelbooks into English through glosses written between the lines of the Latin texts. By the year 1000 parts of the Bible were being paraphrased in local languages with extensive illustrations, as in the Junius Manuscript—word and image working in harmony to expound the meaning of scripture.

|

|

Click on an image for details:

Codex Zographensis

Ethiopic Gospelbook

Saint Ephrem's commentary on Tatian's Diatessaron

Greek–Arabic Diglot of the Psalms and Odes

The Junius Manuscript

Georgian Gospelbook

Armenian Gospelbook

|