The Gamelan Project: Teaching, Playing with, and Learning from American Schoolchildren Playing Balinese Gamelan

Abstract

The Gamelan Project is a research study that investigates the significance of the human capacity to synchronize, or co-process, time. Balinese gamelan, perhaps more so than any other musical tradition, requires tight synchrony among players as they perform interlocking rhythms at fast tempi. Our research has found a connection between the ability to synchronize with an ensemble in a gamelan-like setting and other cognitive characteristics, particularly the ability to focus and maintain attention. Our current work explores whether improvements at interpersonal time processing, or synchrony, may translate into improved attention. This paper focuses on the development of this project out of a larger elementary school gamelan program and explores the significance not only of possible findings but also of conducting this type of research in the classroom.

Synchrony

She sat upright, deftly striking the tawa tawa, left hand lightly muting the instrument. She appeared both engaged and relaxed, reminding me of the casual mastery that many Balinese ensembles exude. Her fifteen classmates sat arranged in a V formation at the variety of bronze-keyed metallophones and colotomic gongs that make up the Balinese gong angklung ensemble. The intricate, interlocking structure of “Capung Gantung” (The Hovering Dragonfly) hung in the air around us. The tawa tawa is a “time keeper” for the ensemble, and the little girl in question seemed extremely pleased to be playing it, relishing the responsibility of keeping time for the group.

There was just one problem: she had lost the beat. Not a minute into the piece, and with no warning, her tempo suddenly lapsed, sending the entire ensemble lurching into chaos. I tapped the beat insistently on the kendhang (drum), and some ensemble members picked it up, but others had become hopelessly lost. She continued to play with the same expert air, seemingly unperturbed by the chaotic sounds around her. After signaling the ensemble to stop with a drum cue, we began again. This was a third-grade gamelan class at the Museum School, a charter elementary school in San Diego, California, where a Balinese gamelan program has quietly (or perhaps noisily) thrived for the past sixteen years.

More than one thousand children have participated in this unique program, founded by the late Robert E. Brown and funded in part by the Center for World Music through a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Many more children and adults throughout Southern California experienced the Museum School’s gamelan ensembles through their many performances of Balinese music and dance.

A description of someone making a mistake might seem like an unlikely starting point. It is often from moments like this, however, when things fall apart and hitherto hidden dynamics or beliefs may be exposed, that one can learn the most. This particular moment, as explained below, was a turning point that led me to investigate links between Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), rhythm, cognition, and gamelan. While our little group, when not falling apart, sounded much like a group of like-aged Balinese children, we found our own peculiar ways to fall apart that pointed to perhaps a different understanding of the music. The gamelan program at the Museum School has experienced many sudden stops and starts—both literal and metaphorical—as the school, its teachers, and especially its students strive to incorporate this very compelling music into their lives as a cultural object, educational tool, and school tradition. This paper describes that journey, the program, and research and performance projects that have emerged from it.

Background

The gamelan program at the Museum School has its philosophical roots in Mantle Hood’s well-known concept of “bi-musicality.” Just as one who is bi-lingual must have fluency in more than one language, one must be fluent in more than one musical language to be considered bi-musical (Hood 1960). Robert E. Brown, who studied under Hood at UCLA and subsequently founded the Center for World Music, made his first efforts to bring world music, a term he is credited with having invented (Williams 2010), to the elementary classroom in 1973 through his “world music in the schools” program in the San Francisco Bay Area.

In 1999 Brown explained to me that part of this effort was directed toward bi-musicality. Most students of ethnomusicology only encounter musics such as gamelan in their late undergraduate or early graduate studies. For most of them, this is rather late into their cognitive development, at which point it might be difficult to play, or even listen to, unfamiliar music with unbiased ears. Brown’s simple yet groundbreaking solution to this issue was to start children out earlier, much earlier. What would happen if American children started gamelan or Carnatic music in elementary school? How would they understand this music? Aside from the very small fraction of such students who might actually become ethnomusicologists, Brown posited, all students who encounter music of another culture would benefit through increased cultural fluency. The original world music in the schools program, though spectacular, was short-lived, and Brown—together with his Center for World Music—moved to San Diego in 1979. Twenty years later, I found myself working with Brown to reestablish this program. We began with a Balinese gamelan program at the Museum School.

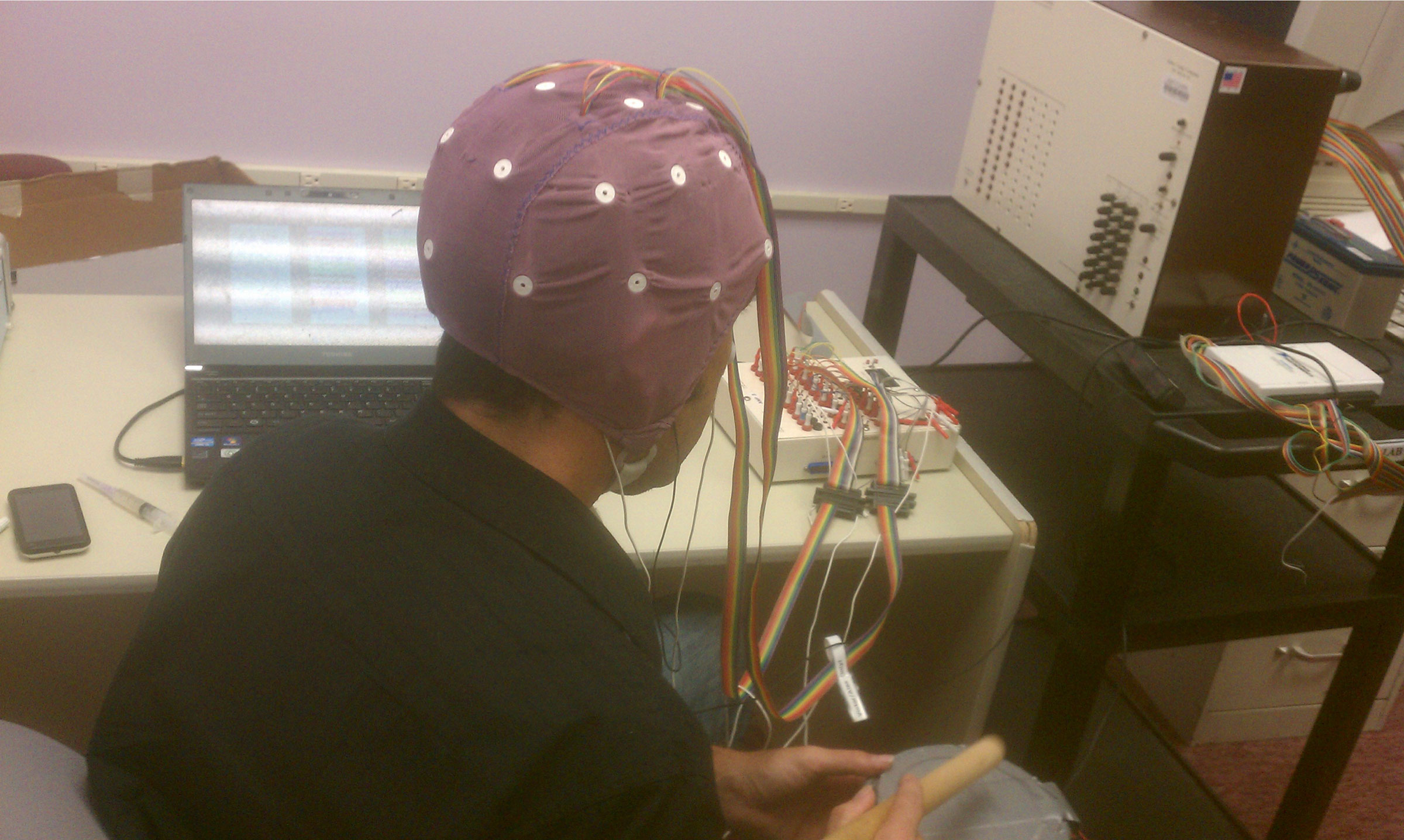

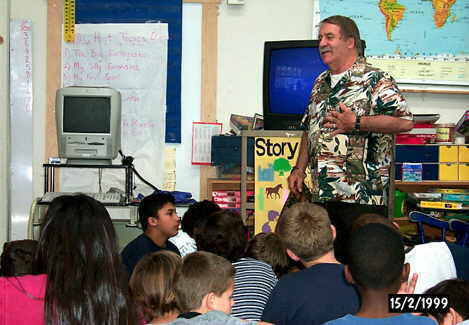

The Museum School was founded by Carl Hermanns, a former symphony conductor, in the belief that music and other creative activities are fundamental to human development and education. This public school with free tuition was attended by students from diverse backgrounds. Its gamelan program was originally intended to last for only two months. Brown arranged for two Balinese artists, I Nyoman Sumandhi and Ni Putu Sutiati, to instruct (fig. 1). Kaori Okado and I, who had been on tour with them performing wayang kulit, assisted. Okado had studied gamelan and dance under I Nyoman Wenten as a dance student at the California Institute of the Arts and had since studied in Tunjuk, Bali. Students from third to sixth grades were taught gamelan gong angklung and dance three times a week with the goal of a performance at the end of the two-month period. The program was well received by the school, the children, and the parents.

Brown’s generous and indefinite loan of a gamelan enabled Okado and me to continue teaching the classes after the two-month period (fig. 2). Brown and I applied for and received funding from the National Endowment for the Arts to expand the World Music in the Schools program. In its new iteration, the program featured a tiered design. Schools could choose their level of involvement depending on time, facilities, and the other resources they could commit. Schools at the highest level of involvement hosted an ensemble and a teacher for an entire school year, included this teacher’s music in their curricula, and developed a performing ensemble that participated in performances for other schools. Schools at lower levels of involvement hosted a teacher for a brief residency, a workshop, or simply an assembly-style concert. This would hopefully feature the teacher performing together with an ensemble of students from a school with a high level of involvement.

The energetic gamelan program at the Museum School was the inspiration for this design and was also the most central participant. While Ms. Okado and I continued to teach, a number of guest teachers, including I Madé Lasmawan, Ni Ketut Marni, I Nyoman Wenten, Ni Nanik Wenten, Casey Lee, Wuri Wimboprasetya, Adam Berg, Tyler Yamin, and I Putu Hiranmayena completed residencies at the school. By 2003 every child in the school received one hour of in-curriculum gamelan class weekly, and there were three levels of after-school gamelan, with the highest being the Puspa Warsa performing ensemble. Some students were so heavily involved with the after-school program that they were playing and dancing as much as seven hours each week. Noting the growing gamelan culture at the school, Brown expanded his instrument loan to include a gong kebyar ensemble and two Javanese gamelans. Puspa Warsa performed regularly at other local schools, music festivals, and fairs, and it was frequently invited by the consulate general of Indonesia, located in Los Angeles, to participate in its events. The largest local activity was the school’s annual Gamelan Festival, a fundraising event that featured not only performing groups but also recital-style performances at each grade level.

We were all saddened when Bob Brown suddenly passed away in late 2005 (fig. 3). In his memory, I Nyoman Wenten renamed the ensemble Giri Nata (Hermit Mountain) in reference to Giri Kusuma (Flower Mountain), Brown’s much-loved residence on Bali. All of Brown’s gamelans, which by this point were in use at the Museum School, were bequeathed to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Suddenly without instruments, the school struggled to maintain the gamelan program. Fortunately, with the help of Working Arts, the Center for World Music, and several parent donors, we were quickly able raise enough funds to purchase a gamelan angklung from I Madé Lasmawan.

Sixteen years since its inception, the gamelan program at the Museum School continues. Some of the original students—a few of whom now have children of their own—still play and dance. (It would be interesting to know how these bi-musical individuals would fare as ethnomusicologists, but none of them has yet taken up the subject!)

Pedagogy

A goal at the Museum School from the start was to institute traditional Balinese pedagogy—that is, maguru panggul, or “teaching through the mallet”—as much as possible. As the name implies, maguru panggul refers to almost entirely practice-based learning. The teacher plays, often at or near performance tempo, the students try, and the process repeats (fig. 4). Although “rote learning,” a term that is applied to a variety of practice-based forms of learning that rely on some form of imitation, is less than popular in the United States today (Cushman 2012), learning music in this way does have many advantages and clearly helps refine listening skills and tonal memory. In spite of the strengths of the maguru panggul style, our students—coming from radically different backgrounds—needed some adjustments to the approach to make it work for them.

Although Balinese children of comparable age might never have played gamelan themselves, they will be quite familiar with it, whereas American children have likely never heard any gamelan at all. It is critical to emphasize the importance of this difference. If one plays a melody that starts on an upbeat for a group of Balinese children, for example, they will already know where the beat is. A group of American children will not. Balinese children learning to play gamelan are learning to reproduce sounds they have heard throughout their lives. American children will likely not have any idea of what a given piece will sound like once all of the parts are layered in. This presents a unique challenge for them. Without a clear goal in mind, it is difficult to know when one is playing correctly. For our teachers this means providing, and constantly reiterating, context by teaching interlocking parts while an assistant plays the beat or basic melody.

Additionally, some children find the sound of a full gamelan overwhelming and are at first unable to parse it into separate musical structures. To facilitate this, we developed a number of musical games that involve such things as listening for drum cues and stopping, counting notes or beats played by someone on a different instrument or part, or staying on beat when the leader varies the tempo at will. The games heighten engagement and allow children to focus on specific parameters of the music (e.g., tempo or other player’s parts) without the added challenge of playing an entire piece (fig. 5).

An important observation is that some of the differences between Balinese children and American children were muted a few years into the program when incoming students would frequently attend performances by our veteran ensemble. By hearing and seeing the ensembles practice, the new students became more “natively” fluent than the previous generation of students who had to start at zero. This was particularly evident in a general decrease in learning time for pieces and parts in younger students after the program had been established for a few years.

Another difference in pedagogy involves the actual playing technique: how one holds the mallet, how one’s hands move when striking or muting gamelan keys, or even how close to an instrument one ought to sit. In traditional Balinese pedagogy, this is rarely discussed because Balinese children have seen many gamelan players and even sat in a parent’s lap as he or she played. Since our American students have little to no exposure to Balinese instruments and music, we provide relatively detailed instruction in technique.

A common means of teaching is to sit opposite a person and play the part from the opposite side of the instrument. Until one learns to think of the arrangement of keys on an instrument as a set of absolute positions, as opposed to left and right, it can be somewhat difficult to do this. Children who learn more quickly than others are asked to move to the other side of the instrument and learn to play from there. Some of these children then help their friends by playing their instruments “from the other side.” This is helpful as it provides a visual reference for children who are learning, and since the class will not move forward until every student has learned his or her part, this also keeps the advanced students engaged (fig. 6).

Repertoire

Repertoire at the Museum School has changed significantly over the years. This is in part due to changes in available instrumentation, but it also reflects changes and preferences of the group’s various dance teachers. The ensemble has avoided dancing to recorded music and, as much as possible, has danced to live music. Traditional pieces have included “Pendet,” “Panyembrama,” “Puspa Wresti,” “Rejang Dewa,” “Margapati,” “Manuk Rawa,” “Baris,” “Topeng,” “Liar Samas,” “Jaya Semara,” “Sekar Gendot,” “Tabuh Telu Nding,” “Capung Gantung,” and “Bapang Selesir.” I Madé Lasmawan was very helpful when Giri Nata switched to the ten-keyed kebyar instruments to the four-keyed angklung. He had already transposed many of our repertoire pieces, and we were able to learn some of these from him.

The Balinese kreasi baru (new creations) compositions have been especially popular within the Museum School gamelan program. Balinese gamelan is a living tradition, and being alive by definition involves the ability to respond to one’s environment. It follows, then, that a new environment would be reflected by new music. The first kreasi barupieces learned by the ensemble were composed by I Madé Lasmawan (fig. 7). “Kreteg Layang” (The Flying Bridge) features an instrument created specifically for this piece and a small ensemble of Western instruments. Created by Lasmawan to represent a mix of East and West, this piece became jokingly known as our lagu negara (national anthem) because of its (over)frequent playing. We also learned “Pakeling” (Reminiscence), another of Lasmawan’s pieces, which incorporates baleganjur and angklung instruments.

Our ensemble created some of its own kreasi baru as well. “Gendhing Gembira” (The Happy Song) was composed by Museum School students and paired the Museum School gamelan with its rock band featuring two guitarists playing interlocking “power chords.” “Singha,” which I composed as a memorial for family members of several of our players, featured complex, polymetric interlocking parts and a baritone saxophone.

Discussion

“It’s fun to learn another culture’s music because then you can kind of speak with them, in a way.” –Olivia, Museum School student, age 9

“One dance I did was called baris and that was like a warrior dance and it was the first dance I ever did in public and that one changed me because it taught me how to learn, how to memorize something that you do.” –Andrew, Museum School student, age 8

Video 1. Students at the Museum School share their thoughts on gamelan (recorded in 2002).

What has resulted from the Museum School music program on which so much effort, time, and money have been expended? What implications might these results have for education on a larger scale, keeping in mind that only a fraction of schools has the special combination of resources that would make such a program possible? I address these questions in two main areas: cultural fluency and music cognition.

Cultural Fluency

The student population at the Museum School is extremely diverse; multiple ethnicities are represented and several languages are spoken. It is somewhat surprising then that Museum School students frequently use the word “other” in referring to Balinese culture, particularly given that they did not seem to consider the many Balinese people they met and successfully interacted with, including several children their own age, as “other.” It would appear that while these students do not perceive a significant distance between themselves and Balinese people, they do perceive a distance between themselves and the Balinese culture from which gamelan emerged. This is, in many respects, also true of the Balinese people, who frequently cite sacred and/or mythological origins for their performing arts (Herbst 1981).

In our efforts to incorporate Balinese gamelan into the overall culture and tradition of the school, with the exception of a few specific groups (see Khalil 2010), we did not include much explicit instruction in Balinese culture, values, belief systems, history, or geography. This was not because we did not feel these things are important: we simply did not have enough time. In spite of this, the students showed a remarkable ability to understand many aspects of Balinese culture simply by playing the music, learning about the pieces they were performing, learning the names of the instruments, and learning a few musical terms, such as cengkok, pokok, and koték.1 Museum School gamelan players understood the organic unity to which Balinese music aspires, describing Balinese gamelan players as “showing off” their “teamwork” or “coordination,” and aspired to do this themselves.

Perhaps a more direct and more relevant measure of cultural fluency and understanding would be bi-musicality. Were Museum School students able to achieve a level of bi-musicality in their studies of Balinese gamelan? As hinted above, there is more to learning a different culture’s music than simply starting to play it early. Although the Museum School students began learning gamelan at approximately the same age as their Balinese counterparts, and although they might even have had similar amounts of practice time and experienced similar pedagogy, they were starting out in significantly different circumstances.

By the end of their first year of life, children’s perception of such things as language, music, and even faces narrows to match the statistics of the world around them (Flom 2014). This process, known as perceptual narrowing, is helpful in that it improves perceptual discrimination of familiar stimuli. Through the process of perceptual narrowing, unfamiliar scales, rhythms, and timbres become more difficult to discriminate from each other. Even starting gamelan in kindergarten, as many Museum School students do, is quite late in this process. Some recent studies have shown that the period of perceptual narrowing can be extended or that the process can even be reversed. Perhaps sufficient exposure to Balinese gamelan may allow previously unexposed kindergarteners to come to perceive the music in much the same way that Balinese children do (Friendly 2013).

A difficult question surrounding the concept of bi-musicality is the notion that different cultures perceive musicality in different parameters of music (Hood 1960). For example, Turkish music highly values subtle differences in pitch and complex modal modulations, whereas Japanese music highly values timbre. For each of these cultures, and for performers to play with musicality, they must have a deep understanding of and control over the culturally appropriate parameters. I posit that in Balinese music, musicality is more temporally based. A crucially important component of Balinese musicality is synchrony, the ability to time movements precisely with others. While at first this may seem obvious, it might be difficult for a non-Balinese musician to grasp this in an experiential or affective way—to be moved by tight synchronous playing in the same way that someone from a western European tradition might be moved by lyricism.

There is something very un-Balinese, or at least very un-musical in a Balinese sense, about the scene described above of our little third-grade gamelan ensemble falling apart by having a member suddenly become deaf to aural and social cues around them. While this suggests the possibility that these children had not completely achieved bi-musicality, there is another temporal component of Balinese musicality that they seemed to understand readily: tempo. Older accounts of Balinese music often describe the music as being repetitive, since on paper many pieces reduce to simple melodic sequences of only a few beats long (McGraw 2008a). This Western view of Balinese music, however, overlooks the importance, from the perspective of Balinese musicians, of tempo changes in providing overall structure to a piece. The Museum School students clearly understood this, as they were happy to play such “repetitive” pieces and found the tempo changes quite exciting. Several times I have witnessed a disconnect between parents and students in this area. A parent will complain that all the students did was “play the same thing over and over again,” and a child will adamantly respond that this was not true, that the music “changed” quite a bit.

While it may be argued that the Museum School children have not become completely bi-musical, they certainly understand Balinese music to some extent in a Balinese way, and this understanding gives them access to other aspects of Balinese culture and aesthetics.

Gamelan, Synchrony, and Attention

Let us now return to the subject of the little girl losing the beat, that is, falling out of synchrony. This precocious third grader had been in my gamelan class at the Museum School for almost a year. She was also an enthusiastic member of our after-school gamelan program. She was talented musically; she could learn new pieces with relative ease and was a quick study with instrumental technique. She was engaged with the class, too. She took pride in knowing the names of all the instruments, she could demonstrate a variety of dance movements, and she had even produced several gamelan-themed paintings that adorned our practice space. Despite her talent and enthusiasm, however, one thing appeared to remain elusive—synchrony, the process of aligning herself in time with what everyone else was doing. I knew several other children who fit this profile. They were highly engaged, talented, and motivated, yet they struggled to synchronize with everyone else. It would not be surprising for a child who is disinterested, disengaged, or even oppositional to have difficulties with playing, including synchrony, since engagement and effort are necessary to learning. For these children, neither interest nor effort appeared to be in short supply. Further, it could not be said that they simply lacked musical ability—they were good in areas other than synchrony. On this particular occasion, as I watched this girl lose the beat, I suddenly realized that she—and the other children I knew who fit this profile—were all children who had been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

I had been somewhat skeptical of ADHD. While I did not question the existence of the condition, or conditions, I was uncomfortable with the explosive rate at which ADHD was being diagnosed. I was further uncomfortable with the seemingly preferred treatment centered on powerful stimulant drugs, such as methylphenidate (Ritalin). Compounding this, the children whom I knew to have been diagnosed with the condition seemed in my music classes to be perfectly fine: they were engaged, well adjusted, and well behaved. I was often surprised when their parents would tell me of behavioral and scholastic problems and an eventual ADHD diagnosis. While such problems were not apparent to me in music class, the inability to synchronize rhythmically—in spite of often strong musical abilities—stood out in these children. Here was an issue that seemed to me more tangible and recognizable than the complexities of behavior or scholastic performance: this was something I could hear.

As with the third-grade girl, other Museum School students who had been identified with attention issues appeared to be generally engaged and enthusiastic about gamelan, so it did not seem that their obvious difficulty synchronizing was due simply to a general lack of attention or compliance. Would it be possible to measure what I was hearing? Could impaired timing, specifically in the form of difficulties in synchronizing, be a biomarker for attention problems? Furthermore, and even more exciting for a music teacher, could improvements in timing achieved through musical practice like gamelan translate into improved attention generally?

With these questions in mind and having just completed my PhD in music, I delved into literature on ADHD in psychology and neuroscience. To my surprise, I found significant amounts of literature on impaired temporal processing and ADHD (for a review of much of this literature, see Toplak 2006). Further, the evidently close relationship between temporal processing and attention aligns with the theory of dynamic attention, which describes attention as a process that depends on the ability to identify temporal patterns and predict important points in time (Jones and Boltz 1989; Large and Jones 1999). According to dynamic attention theory, sensory discrimination is enhanced when events happen at predictable points in time. When the object of attention is more predictable, sensory discrimination will be facilitated through dynamically modulating attention to follow its pattern. Perhaps more importantly, however, the better an individual is at perceiving and predicting temporal patterns, the better her capacity for perceptual acuity generally. For example, enhanced temporal processing has been shown to correlate with better understanding of speech in social settings and in noisy situations (Song 2011). Because different cultures prefer different temporal patterns in speech, music, and gesture, the ability to perceive and predict these patterns must be learned—or at least refined—during the course of development. In this way, the act of learning music with others may help “calibrate” the nervous system for a given cultural environment. Within the extensive body of literature on ADHD, or on attention in general, and temporal processing, little work exists relating to the type of coordinated interpersonal temporal processing required in such musical contexts as gamelan.

These initial investigations drew me into the field of cognitive science. I was accepted into the department of cognitive science at the University of California, San Diego, as a postdoctoral scholar as well as a trainee at the Temporal Dynamics of Learning Center, a Science of Learning Center with the National Science Foundation. I initiated a new research project, which has come to be known as the Gamelan Project, directed toward investigating cognitive development and interpersonal timing. Under the guidance of Andrea Chiba, a multidisciplinary team was organized to conduct the project. It includes Victor Minces, a computational neurobiologist, Grainne McLoughlin, a psychologist and geneticist specializing in ADHD, and myself.

Our first goal was to test whether my observations—of a link between attention and rhythmic synchrony—could be measured quantifiably. A key challenge was to find a way to measure synchrony that matched the way human beings actually experience it: as a collaborative process. As anyone who has ever tried to practice with a metronome knows, synchronizing with its unyielding pulse is a different experience from synchronizing with a human being. People adjust for each other. For the purposes of our study, this meant that it would not be enough to record kids playing with a metronome or use a metronomic beat as a standard for comparison. The solution lay in a technique called Vector Strength analysis (VS) and had been used extensively by Minces to measure synchrony of firing neurons (Goldberg and Brown 1968).

Most musical rhythm is cyclic in nature. These cycles can be considered as oscillations. VS measures the difference in phase between any two oscillations. The more in-phase they are, the more synchronous they will be, regardless of whether the rhythmic events in question are happening simultaneously. By using VS to measure synchrony among players, we could record students playing together in the natural environment of a music class and have a measure of how well each student was synchronizing (video 2).

Video 2. Vector Strength analysis measurements performed in real time.

When measuring VS, a display in the lower right-hand corner of the screen features concentric rings and a white sweeping line that resembles a “radar sweep.” Each ring represents one player, with the outermost ring being the teacher. The beat, driven here by the teacher, is represented by the clockwise “radar sweep.” Each time a student strikes the instrument, a colored dot appears on the screen. If the strike is exactly in time with the teacher, it will appear at the 12:00 position. If the player is ahead, it will appear to the left, or if behind, to the right. If the player is exactly on the offbeat (anti-phase), the dot appears at the 6:00 position. The dots leave white traces. The spread of these traces indicates VS, that is, how well each player is in phase. The wider the trace, the poorer the VS; the narrower the trace, the stronger the VS. In the first segment of the video, the group synchronizes to an isochronous beat. In the second segment, the students play a melody. The color of the dots indicates which note each student is striking. This visualization and the methods used to create it is described more fully in More Playful Interfaces (Mullen 2015).

We gathered 102 children from the Museum School, placed them into like-aged groups of twelve students, and recorded them synchronizing with each other. Each student also underwent a series of cognitive tests for attention, and each student’s homeroom teacher filled out a questionnaire for attention behavior. As predicted, the attention scores on tests and questionnaires correlated with VS scores across the full continuum of performance. The best attenders were also the best synchronizers, and the poorest synchronizers were the poorest attenders. The results and methodology of this study were published in Frontiers in Psychology (Khalil and Minces 2013).

This first study confirmed my observation that a correlation exists between the ability to synchronize and attention. It does not, however, answer the question of whether improving synchrony through rhythmic training might result in improved attention generally, nor can it answer the question of whether the observed correlation is due to impairments at temporal processing or poor attentional allocation. Perhaps, as suggested above, those with poorer attention control synchronize more poorly because they are simply not paying attention. Our current and ongoing efforts are directed toward each of these questions.

To test whether attention can be improved through improved synchrony, we are preparing longitudinal studies. These studies will involve teaching gamelan to a group of children, testing them with a variety of attention and cognitive tests before and after the period of gamelan instruction, and comparing these results with those of a group of age-matched children who did an activity different from gamelan.

One might ask why gamelan has come to be an important part of a study that focuses on a relatively basic aspect of music cognition. It would be easy to assume that in selecting such seemingly exotic music to work with, we are appealing to the existence of some peculiar, perhaps mysterious component of this music that might produce hypothesized effects. The truth, however, is more mundane: our project focuses on interpersonal synchrony. Few musics match gamelan in its focus on this particular component of music. Furthermore, gamelan instruments readily lend themselves to measurements of this synchrony. Marta Kutas, chair of the cognitive science department at UCSD, remarked, “It would be difficult to design instruments better suited than gamelan for measuring group timing.” The fact that we happened upon this music is also hardly coincidental. My observations of children falling out of synchrony were probably made possible by the fact that they were playing this music.

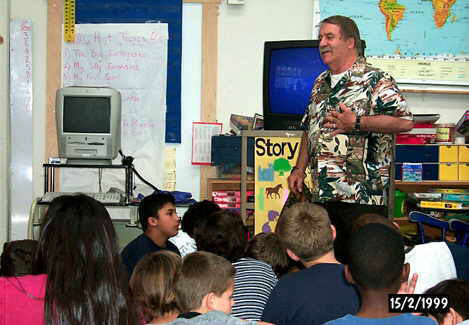

Under normal circumstances, performance at any given task, such as synchronizing with a group, is dependent in part on the degree to which a person is engaged in the task. For this reason, it is extremely difficult to compare measures of attention control with measures of performance at any task. In order to bypass this confound, we are using electroencephalography (EEG) to measure directly nervous system response to rhythm (fig. 8). Subjects are not required to do any task. Rather, they watch silent cartoons as a series of beats is played to them on headphones. We measure the way the brain responds to beats that are “jittered” or “off” in some way.

Conclusion

While the gamelan program at the Museum School represents an effort to foster bi-musicality, to promote cultural awareness, and even to understand related aspects of music cognition, it is important to note that it is first and foremost a musical effort, directed simply toward teaching and learning Balinese gamelan music.

A growing body of scientific evidence suggests that the practice of music is related to and may impart a number of perceptual and cognitive benefits. (For a review of this literature, see Strait and Kraus 2011.) These benefits, however, are hardly central to the experience of playing music, nor are they perhaps ever cited as motivation for playing it. Music holds a peculiar place in our lives. Its sound is easily encoded and readily reproduced by all kinds of devices that pump and push it into every part of our waking, and even sleeping, lives. In spite of this ubiquity, which imparts a sense of music as being mundane and commonplace, the experience of this sound, the emotion that it engenders, remains elusive and even difficult to describe in words. This is not to say that music, being mysterious and elusive, is unavailable to scientific study. Rather, we believe that the scientific study of music can benefit from this poorly understood connection.

As a scientific study, the Gamelan Project is still in its early stages. We have so far established that a correlation exists between attention and the ability to synchronize. The possibility that a causal link exists between these two capacities, while exciting, remains untested. In spite of this, it is clear that programs like this one are beneficial in that they engage students and enrich their lives. Further, this engagement might be a critical factor for achieving other types of gains. Aniruddh Patel, in his OPERA hypothesis, posits that the experience of emotional engagement (the E of the OPERA acronym) is one of five conditions necessary for musical training to improve neural encoding of speech (Patel 2010). The idea that engagement with music is a necessary condition to its cognitive benefits highlights the importance of ecological validity in scientific studies of music. To really test this hypothesis, students must be practicing music as art for its own sake. Our methodology is grounded in, and informed by, this idea.

It will still be some time before the Gamelan Project may yield further scientific results. These longitudinal studies, as the term implies, will take significant time, and a fairly large number of students must participate to reach sufficient statistical power. Of course, this matters little to the students. For them, it is all about playing gamelan (fig. 9).

Notes

1. Cengkok (“flower”) are ornamentations of the melody line. Popok (“tree trunk”) is a structural melody played by a few special instruments. Koték is the technique of interlocking, or “hocketing,” melodies.

Next: Musical Knowledge, Innovation, and Transmission »